-

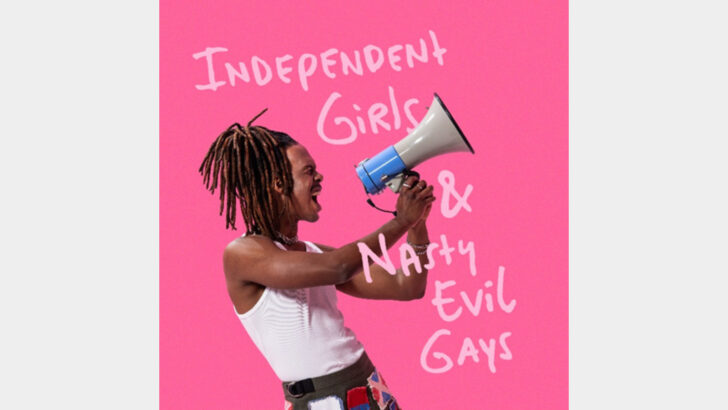

Dutch soul pop star Jeangu Macrooy releases a queer protest song, ‘Independent Girls & Nasty Evil Gays’, out now

-

London Trans+ Pride: this year’s theme is ‘Existence & Resistance’, 26 July ’25

-

“Have you ever held a secret so heavy it felt like it could break the world?” by Sadiq Ali

-

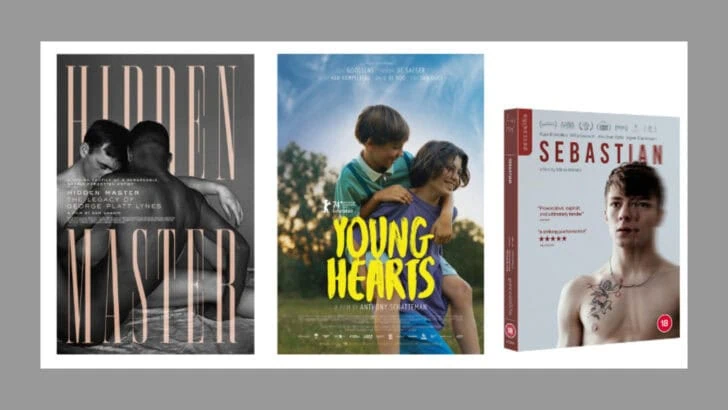

QX July LGBTQ+ film highlights

-

The Post-Pride Practice: When the Rainbow Flags Come Down, Your Real Work Begins

-

Queer Decompress & Born This Way: two workshops for a post-Pride soft landing, 12 July ’25

-

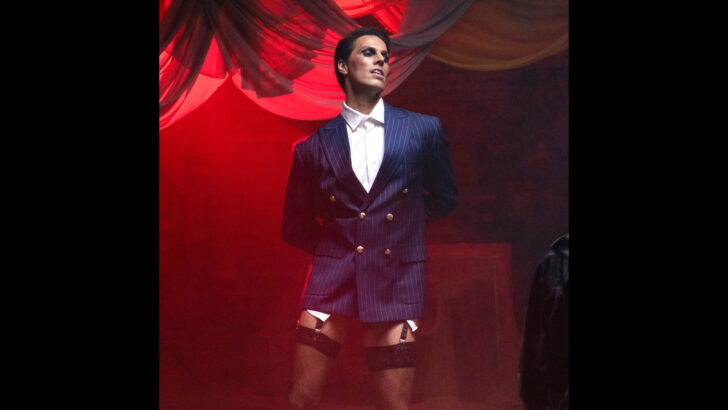

Jordan Luke Gage to star in new musical, Saving Mozart, at The Other Palace, 28 July to 30 August ’25

-

“Queer YA Fiction and Coming Out” by Poppy T. Perry

-

“From Diagnosis to Disco: How Cancer Led Me to OutPatients and Back to the Dance Floor” by Daniel Edwards (aka DJ Dallyn)

-

Pride as a Spiritual Practice

-

“From Performativity to Body Politics: The Metaphorical Myths and Rituals of Artist Scarlett Wang” by Freya Fan

-

Window Shopping at Bonnington Gallery

-

QX meets Worricka, queer singer, songwriter and artist

-

Kfir debuts Glamorous: a bold, disco-driven ode to identity, style and self-worth

Stories

Welcome to the QX Magazine blog, your go-to destination for engaging LGBTQ+ stories, news, and lifestyle content. Here, you’ll find a diverse range of articles covering everything from the latest LGBTQ+ news to insightful features, travel tips, and entertainment recommendations. Our mission is to celebrate and support the LGBTQ+ community by providing you with informative and entertaining content. So, grab a cup of tea and join us as we explore all things queer!