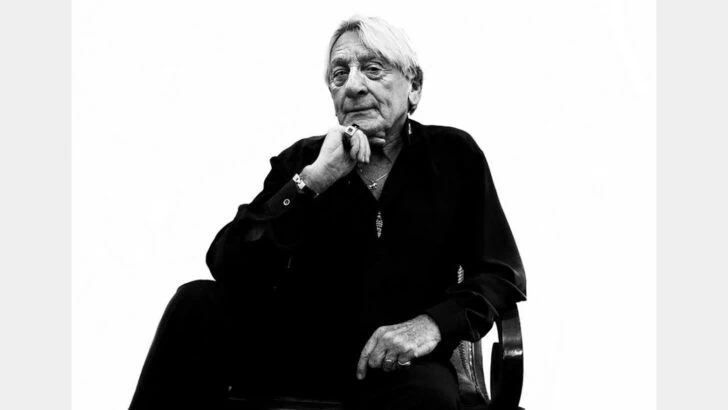

Xav Judd talks to Kenya’s David Kuria Mbote, who is hoping to become Africa’s first openly gay black politician in March’s senate elections…

If you’re gay, there’s not a worse part of the world to be living in than Africa. Homosexuality is banned in over 75% of her states and one can actually receive the death penalty just for being who we are, in three of them. Nonetheless, Kenyan David Mbote is seeking to become the first openly non-straight black man to hold national office in the continent, if he wins in his country’s senate elections this year.

A devout catholic who once trained as a priest, the 40-year-old’s decision to run is courageous as it carries great personal risk. Homosexual ‘offences’ in his homeland carry penalties of between five and fourteen years imprisonment. Added to which, only in November 2010, the Kenyan prime minister, Raila Odinga, said the behaviour of gay couples was “unnatural” and that “if found, the homosexuals should be arrested and taken to relevant authorities”. The Kaleidoscope Trust recently brought David over to London for the Leadership Forum Lecture at University College. We interviewed him to find out about his background and ask how he was inspired to break into politics…

Where did you grow up?

In a village known as Mang’u which is in one of the largest counties in Kenya, Kiambu – 1.6million population.

What was your childhood and adolescence in Kenya like and what difficulties did you face other than those related to your sexuality?

Growing up in a farming community [David’s mum was involved in agriculture; his dad was a banker] was arduous; I had to pick coffee, normally on Saturdays or during the school holidays, which was particularly difficult especially in the rain. At the time our village did not have electricity or running water, so we had the demanding task of fetching the latter from a borehole.

What was the money situation like when you were growing up, was it a tough existence?

Due to dad’s job, I would not say it was particularly dire: we were one of the very few families – less than 10 – who had a car and lived in a permanent house. That, though, meant I had an acute awareness of inequality, especially given the poverty and need of other households around us.

“There were occasions when people would not even share a lift with me.”

How old were you when you first thought you might be gay, and how did you cope with this?

I grew up being very naive about sexuality, because my society did not have the conceptual construct of gay and straight. In our biology classes we learnt about body changes like hair increase and breasts for girls, so when in high school I became sexually conscious – and messed about with male friends – I thought these types of experiences were just what happened to everybody, but once ready to marry one becomes heterosexual.

In my teenage years at major seminary [a religious school], however, I began to realize I was different, and at the time discussed it with a friend. He confided in me that he had never had feelings for other boys, so I began to accept that I was gay even though it was in the context of living as a celibate priest in the future.

Why did you decide to come out?

After leaving the seminary I found work with an anti-poverty NGO. I came out to two of my office colleagues, because they had recently married and we could not retain the kind of social life we’d had before. They felt if I wed as well, we could preserve our friendship. Their pressure on me to tie the knot forced me to tell them. One of them was very supportive to the extent of suggesting I date a very effeminate – but straight as it turned out – man who lived near his home.

Were you close to your family growing up? How did they react to your sexuality?

Yes, and we still remain very close. Nevertheless, as with some friends, when I came out and to this day, my relatives chose not to talk about my sexuality.

What about the wider community, was there any response from them? Did you experience prejudice or even violence?

There has not been any obvious or direct response including where I currently live, despite everybody knowing about me. Nonetheless, during my days at GALCK – Gay and Lesbian Coalition of Kenya – there were occasions when people would not even share a lift with me, even though we would be going to the same meeting.

Why did you decide to get involved in politics, especially knowing the potentially severe personal risks?

Being surrounded by poverty gave rise to a deep commitment to social justice. I remember while in the seminary, I was an active member and eventual leader of the Option for the Poor group. And I have always been interested in politics because it provides a platform to enable social change.

“I have always been interested in politics because it provides a platform to enable social change.”

How much of a barrier is your government and church’s stance in blocking gay peoples’ quest for rights in Kenya?

The church can be quite vocal and dismissive of gay peoples’ rights. Indeed, they believe such rights “have even been rejected” by the Kenyan people. The government, on the other hand, is quite schizophrenic in its response. On the one hand, you have the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights – a government body calling for decriminalization of homosexuality – but counter to this progressive approach, the police constantly harass people.

What are your thoughts about the Kenyan government and church’s responses to HIV transmission?

The government response to HIV/AIDS interventions has in some cases been remarkable e.g. ending vertical transmission and trying to reach out to people in need of treatment, but in other instances quite timid. In fact, we know of structural barriers such as laws criminalizing MSM [men who have sex with men] and sex work, which prevent members of the key population from being attended to in the appropriate manner. There cannot be any debate whether these [obstacles] need to be removed, but the government is intimidated, in particular, by religious leaders.

The church’s response has been absolutely abysmal. Occasionally, they do provide treatment and, in some cases, home-based care and support for those with HIV/AIDS. Notwithstanding, the institution is terrible when it comes to reducing stigma against infected individuals and members of the key populations such as IDUs [injecting drug users], sex workers and MSM, who constitute almost 30% of HIV cases in Kenya. Furthermore, this religious body opposes the removal of the aforementioned structural barriers and various others, one example being IDU’s access to harm reduction interventions.

What would your main goals be if elected, and what are the most vital things you would like to change in relation to LGBT issues?

Firstly, I will seek to implement my five point program: Kiambu Senate Representation; Raising Kiambu’s Investment visibility; Re-engineering health systems; Kuria Foundation for Social Enterprise; Platform for 2nd chances, which would aid all LGBT people.

More directly, however, I would use a political platform to highlight injustice and human rights abuses suffered by LGBT individuals in Kenya and potentially outside of the country. I believe that visiting the victims of such infractions – whoever was responsible, even the police – and publicising their cases or bringing this debate to the floor of the house, might help achieve this aim.

On a personal level, I hope to inspire all LGBT people to pursue their dreams and not let sexual orientation or gender identity be a barrier to their hopes or aspirations.

What do you think about the rest of Africa, with regard to attitudes towards homosexuality?

Each country has its own share of progressives and conservatives, but the tone of the debate is generally set by the most senior leadership, e.g. presidents and ministers. .Often the political class, particularly when unpopular, uses anti-gay sentiments to rally support around them.

The reason why Kenya has appeared to be more liberal is perhaps because President Kibaki has never felt the need to be populist, hence saw no reason to demonize a minority in order to win the support of the majority. There are some political voices even in Kenya, which give one a feel, however, that my nation may not be different from other states in the continent when it comes to intolerance.

• More Information:

The Kaleidoscope Trust: www.kaleidoscopetrust.com