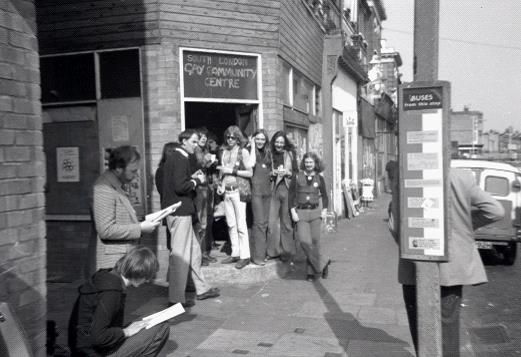

This story begins in 1972 with the formation of the South London Gay Liberation Front and the subsequent squatting of the first-ever Gay Community Centre and squatted gay community. I stress the point that the word ‘gay’ refers overwhelmingly to gay men. I am also using words of this period; hence you won’t see anything of the word ‘queer’, which was seen at the time as an insulting term for homosexual.

The first two years of existence were precarious because of homophobia, including hostile landlords, misguided youths and belligerent pub customers driving us out of various venues. Despite all this, a solid core of dedicated activists was formed, and we campaigned in 1973 in several South London town centres with placards and leaflets proclaiming ‘new kids on the block’. However, by now, it was decided that we needed a space over which we would have complete control and security to put an end to our nomadic wandering. It was at this point we met very supportive people involved in the housing activists’ movement, and we ended up cracking a squat in March 1974 on Railton Road.

Our existence as openly gay people did not come easy in a broken-down, working-class area where unemployment, poverty and racism were rife. A large black population and intense police harassment of mostly black youth, including deaths in police custody and the ‘sus’ laws, complete a picture of an ever-present tension in the area, which finally exploded in the 1981 uprising. Young men passing by the Gay Centre from a local youth club nearby smashed the plate glass windows under a hail of bricks and bottles. From that point onwards, we had to board up with posters still proclaiming who we were. The hostilities died down after a while when it was clear we were here to stay, though with an open door policy, we did have the mad axe man paying us a visit and one or two smaller hostile incidents.

The centre was extremely popular and very well attended. The weekly discos drew in a large crowd, and the coffee bar provided a welcoming space for people to meet, socialise and cruise each other.

Andreas Demetriou organised a modern dance and movement workshop, and we later incorporated some of the dance movements into Brixton Faeries theatre performances. The theatre produced three or four plays, sketches and cabarets, with a recent production of ‘On Railton Road’ successfully capturing the rebellious spirit of the times and the trials, tribulations and sex lives of the Brixton gay community using one of the plays as the centrepiece.

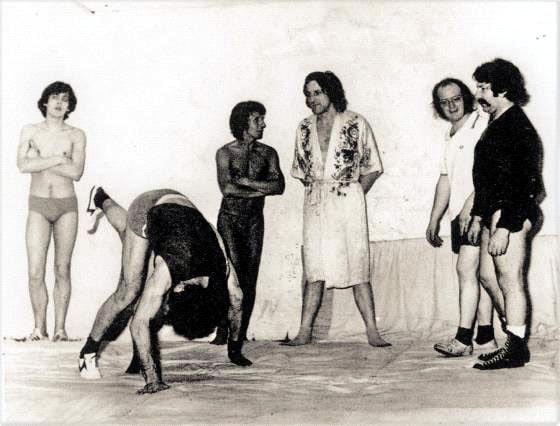

Our wrestling group caused some controversy among gay liberationists at the centre who firmly stood against the male chauvinist, macho values of the grapplers that were seen as oppressive to both women and gays. To counter this intrusion, they organised a knitting circle. The wrestlers were camp as hell and about as macho as a plum pudding.

We stood Gay Liberation Front candidates in the 1974 local and general elections to gain free publicity with a manifesto promising improbably ‘freedom for all.’ Bill Thornycroft’s van toured Brixton with posters plastered on its side, and a loud hailer blared out gay liberation propaganda. Radio interviews and a tour around Brixton market with Malcolm Greatbanks, our parliamentary candidate, extolled the virtues of our programme for gay (and everyone’s) liberation.

In 1976 we picketed a local school, alongside trade unions and left groups, where the fascist National Front held an election rally. Alastair Kerr defiantly held up his ‘Fairies Against Fascism’ placard.

The Gay Centre acted as a magnet to draw mostly gay men into the area and eventually, ten houses were squatted back to back on Railton/Mayall Roads with a shared garden in between. This experiment in communal living proved difficult but rewarding, with people from different classes, race, ethnic and economic backgrounds thrown haphazardly together. The common threads were our fight against gay oppression and the attempt at alternative ways of living to challenge the hetero/bourgeois status quo of Norman Normal and Clarissa Conformist.

The gay centre was evicted in the summer of 1976, but we reoccupied it immediately afterwards. Friendly sources at Lambeth Council had warned us of the eviction date, and we opposed the bailiffs and police when they arrived. It was a token gesture knowing full well that we would be back in the place soon. We celebrated this reopening by building new furniture, a fresh coat of paint on the walls and an open day with tea and cakes for all. The demise of the gay centre came about partly because of funding problems and the refusal of a grant by Lambeth Council for basic running costs, but also factional strife among the centre users and organisers led to its final neglect and closure.

This did not prevent political and social activity from continuing. The gay squats had gradually become the new centre for the Brixton Faeries theatre group and the campaigns that we initiated and took part in.

After jointly organising the 1976 Gay Pride event from the gay centre before its closure, we established the National Gay News Defence Committee HQ in one of the squats to fight against the prosecution of Gay News for blasphemous libel by Mary Whitehouse (1977) and took part in many demonstrations. We joined forces with the Gay Activists Alliance to picket branches of the newsagent W H Smith for banning Gay News from its near monopoly distribution network (1977-78). We campaigned for those who had lost their jobs and against the threatened deportation of a gay man. Apart from the Brixton Gay Community welcoming the Anti-Nazi League March along Railton Road (1978), we picketed Brixton Police Station alongside black activists and parents against racist police violence (1974-78). Some from the community attended demonstrations in solidarity with Grunwick workers on strike for trade union recognition (1976-78).

The police raided the gay squats on two occasions. One was low-level harassment with no arrests. In the other raid, two people were arrested on drug charges when the police noticed cannabis plants growing in the back garden. They were let off with a caution.

The shared garden provided space for collective meals, making music, banner making, planting trees, shrubs and flowers, a place for play rehearsals, making and mending household items, or just hanging out and chilling.

Between 1974 and 1981, Brixton Faeries produced Mr Punch’s Nuclear Family, Out of It, Tomorrow’s Too Late, Gents, Minehead Revisited, A Christmas Cabaret/pantomime, Street Theatre, and several Town Hall shows featuring, among other things, a gay version of the children’s television programme Andy Pandy.

We started a left-wing magazine, Gay Noise, in 1980 and supported the Brixton uprising in 1981. We were out on the streets and issued a joint statement from the Brixton gay community and the gay section of the Brixton Housing Co-operative in solidarity with rioters. The statement was mentioned in Parliament by an irate William Shelton, Tory MP for Streatham.

By the early 1980s, the Brixton Gay Community dissolved as the Brixton Housing Co-operative transformed the squats into single-person units. They are all still gay, but many people have moved on, and the communal/collective spirit has gone.

In conclusion, I believe the astonishing creativity outlined above could only have happened in a collective/communal setting. It is inconceivable that the Brixton Faeries Theatre Group or any of the campaigns mentioned, or all the people who came out as gay through contact with us as a group, could have happened had we remained living in our isolated bedsits, flats or rooms in some else’s house.

The question remains: why did it fail, and are there any lessons to be learned from that period in the gay past for the contemporary LGBT+/Queer Movement?

For a near-comprehensive coverage of the Brixton Gay Community and background history, look at this website. This is still a work in progress and will be added to as we discover more material.

– Ian Townson –