Professor Alison Oram and Professor Matt Cook take you on a journey through Leeds, Brighton, Plymouth and Manchester – from the sixties to the noughties, exploring the northern post-industrial heartlands and taking in the salty air of the seaside cities of the south. They take it from here…

Alison Oram: Why did we want to write this book? A lot of LGBTQ+ history had been written from the perspective of London and even when a national story was being told, it had this implicit default of London, as if the capital could stand in for the rest of the country. We knew from our own experience of living in different cities that this wasn’t the case and we were really interested in how different cities shaped people’s experiences and understanding of LGBTQ+ identity and community.

Matt Cook: And alongside that we became aware of a treasure trove of new archive material, including an amazing bank of oral histories, from the queer community history projects which proliferated in the 2000s and 2010s. In fact it was partly the particular wealth of material in Brighton, Manchester, Leeds and Plymouth that led us to these cities as our case studies.

AO: Partly that, and also because of what distinguished these places. We chose Brighton and Manchester because they’re very well known as gay cities; they’re the places people wanted to move to, to be queer in the sixties, seventies and eighties. Leeds and Plymouth were different in that respect; they gave us another northern city and another south coast city to set against Brighton and Manchester – and they presented a real contrast.

MC: So what we started to do, with our research, was obviously to look at the LGBTQ+ archival material and to record some of our own interviews, but also to think about the histories of the cities themselves – about their economies, demographics, geographies and their histories and traditions. How, we asked, did each urban history relate to the queer history? How, for example, was queer life in Plymouth affected by the naval culture there and the fact it was at quite a distance from other major cities? What difference, meanwhile, did Brighton’s proximity to London make, and the fact it had a lot of sole traders working in service sector rather than the big employers that were a feature of the other cities?

AO: And we were also thinking about change over time, because we wanted to start in the mid-60s when people first started to describe themselves and others as lesbian, gay, or, a little later, trans, and look at how experiences of these identities shifted in the context of expanding student populations, shifting youth culture and radical politics and of course industrial decline in our northern cities especially. These

things, these changes, were experienced differently by different generations – by those who were adults before partial decriminalisation of male homosexuality in 1967, or who came of age during in the context of Gay and Women’s Liberation, for example.

MC: And what was really interesting about that was taking national events like the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, Clause 28 or legislative change in the 2000s and thinking about how they played out in, say, Plymouth as opposed to Brighton. So in Plymouth the 1967 Act was something of an irrelevance because sex between men and sex between women was illegal in the armed forces until 2000. So it was very important for many lesbian and gay people in Plymouth to keep below the proverbial radar long after the 1967 Act. In complete contrast in Brighton there was a really vibrant and actually very visible sub-culture before 1967: people were behaving as if what they were doing was legal, and so it’s almost the reverse.

With Clause 28 there was relative indifference in Plymouth, because people didn’t see why visibility was necessary in quite the way that they did in Manchester and Brighton where a much valued visibility was under direct threat.

AO: Yes, and I think the student populations as well, of Manchester, Leeds, and Brighton had created radical politics as a sort of background anyway, so that queer politics, gay politics, lesbian-feminist politics, were very prominent in all the cities apart from Plymouth, where it was practically invisible. So we see political consciousness varying in the different cities and that affected the way people lived their lives.

MC: This in a way gave us our structure. The first half, which I wrote, looks in detail at each city in turn to really get a grip on the factors that made them distinct. Then, the second half, by Alison, directly compares the three cities in relation to three cross-cutting themes.

AO: Yes: I looked at migration – at how people ended up in these 4 cities and why they moved between them; at ideas of home and family and the difference that local housing and family culture made to queer experience; and then thirdly, I considered how people looked at the past in each place, and so, for example, at a sense of nostalgia for certain periods of time in each place.

MC: The whole book was based on a collaboration between me, Alison and Justin Bengry, who’s a wonderful historian and who worked as a researcher on the project, and then also with these incredible community groups in the four cities. In a way, it harks back to modes of early lesbian and gay history-making in the 1970s. We really hope that the book communicates this sense of connection and collaboration.

AO: And of conviviality: often lesbians and gay men were divided by politics, and trans people felt disengaged or attacked by other members of the queer community, but the book also shows how, at really important points in the past, we’ve come together.

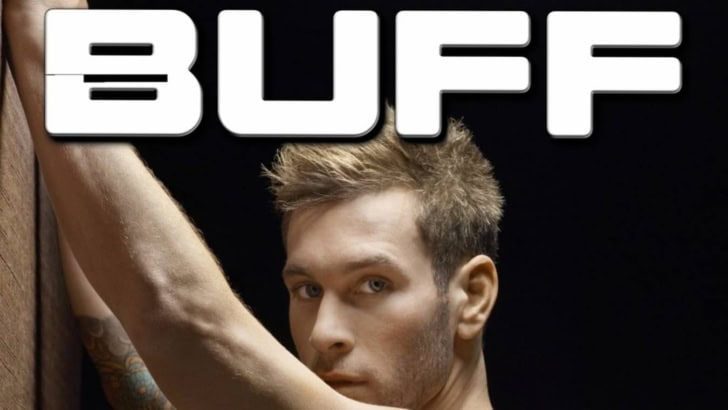

Fill your Christmas stocking this year with Queer Beyond London available to buy from Waterstones and all good bookshops.