You have probably never heard of the writer Mariana Villa-Gilbert. In fact, during her lifetime, few people had heard of her. I certainly knew nothing about her, when in 2020 I wanted to find out about an obscure lesbian novel that had been published in 1968. But it turns out that Mariana Villa-Gilbert is one of our important queer elders.

Mariana – she also went by the name ‘Max’ – was born in 1937. She was the second child of Walter and Ada Villa-Gilbert. Walter was an inventor and manufacturer, and during the Second World War, his factory produced aircraft parts. Mariana’s early childhood was comfortable: a house in the country, servants, a chauffeur. All of that changed in 1944, when her father died suddenly. Ada, who suffered from alcoholism and bipolar disorder, quickly spent the family money. She remarried a Polish RAF officer, who also had mental health issues. In 1947, the family moved to postwar, communist Poland, where Mariana’s stepfather claimed he still had a house.

Dreams were quickly shattered. The family had the last of their money stolen on the journey. When they turned up to the house, it was occupied by another family. Mariana, who was only 10 at the time, spent the next five years living in rural poverty and neglect. She did not go to school. None of the Polish children was allowed to speak to her. She spent most of the time roaming the Polish countryside with her sister. Eventually, she contracted tuberculosis, the British embassy intervened, and she and her sister were taken back to England.

After time spent recovering, and finally going to school (a convent run by nuns), she decided she wanted to go to art school. She studied sculpture under the prominent English artist Elizabeth Frink. But she felt sculpture wasn’t her calling: she was a writer.

Her first book was a thin novel titled Mrs Galbraith’s Air, about a boy who seduces an older married woman. Two further novels appeared, both featuring claustrophobic atmospheres and queer characters. And then came A Jingle Jangle Song.

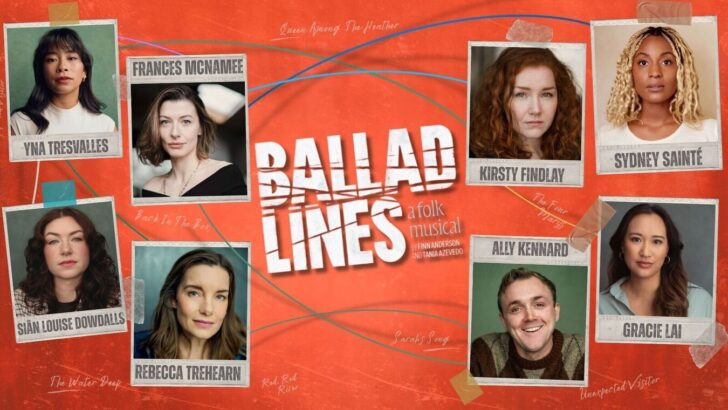

A Jingle Jangle Song is the story of two women. Sarah Kumar is a young, globally famous folk singer: think a female Bob Dylan. She’s breezed into London to do some promo work and play a gig. She wears big sunglasses and spends her time trying to avoid getting mobbed in the street by fans. She is also biracial: her father is British Indian, her mother is Indian, and she moved to America when she was two. Jane Stankovich is an older English woman married to a minorly famous artist (a sculptor, as it turns out). Jane meets Sarah at a house party, and when Sarah passes out wasted on booze, Jane looks after her. Through a series of encounters, Sarah and Jane develop feelings and eventually find themselves in bed together. Events get complicated when Jane’s husband also tries to hit on Sarah. Juicy stuff.

It’s hard for us to imagine, in our era of Sarah Waters’s novels like Tipping the Velvet, and shows like The L Word, Lip Service, and Gentleman Jack, of a time when bi and lesbian representation was almost non-existent. It took pioneering and courageous queer writers to create the world we live in now (though recognising that ‘now’ still has a long way to go). When Mariana sat down to write A Jingle Jangle Song, there had been about 46,000 British novels published in her lifetime. Only about 30 of these centred the experiences of bi or lesbian women. Mariana had almost no models to follow. Of course, there were cheap ‘lesbian pulps’ – paperbacks aimed at straight male readers – but these mostly existed only in the United States. So A Jingle Jangle Song was part of an important new trend in queer women writing about the characters like themselves. A Jingle Jangle Song, along with novels such as Rosemary Manning’s The Chinese Garden (1962) and Maureen Duffy’s The Microcosm (196X), and the lesbian magazine Arena Three (1963-1972), started to create a more open discussion about bi and lesbian women.

When A Jingle Jangle Song was published, male reviewers blasted it for … not appealing to men. One woman reviewer criticised it for being too tame (it’s not: it’s very erotic). But one reviewer – Barbara Grier, who ran the most influential lesbian magazine of the era – recognised it for what it was: a ‘special book’ that was ‘compelling’ and ‘intensely vital’. A book that was a key step in how bi and lesbian women write about themselves.

I got to know Mariana in the last three years of her life. I am a gay man; she was a queer woman. She didn’t ‘do’ the internet, didn’t have a mobile phone, didn’t have a computer. We only met face-to-face twice. Otherwise, she wrote me letters on her typewriter. But despite all that, I’ve come to understand her writing and A Jingle Jangle Song as part of a remarkable moment in queer history.

A Jingle Jangle Song, which has long since disappeared from the book shelves is now being republished by Lurid Editions – a publishing project committed to intentional and conscientious acts of archival repair of the queer literary past. Run by a team who grew up before LGBTQIA+ books became widely and uncompromisingly published and access to queer narratives and stories was limited, they were attentive to how marginalised histories are forgotten and remembered, and are hungry to rediscover the queer literary past for queer readers, for whom books like these fill as much a need for connection with the past as they do an urge to read for pleasure. Lurid Editions patches the gaps and listens to silences, enabling circulation to occur.

A Jingle Jangle Song by Mariana Villa-Gilbert is available once again in paperback from 29 January 2026, both online and in bookshops. You can find out more about the work of Lurid Editions at https://www.lurideditions.com/