My father’s brother’s wife’s brother…. Wait, don’t stop reading, this isn’t a MENSA test. My father’s brother’s wife’s brother was a hairdresser in the 60s. He had delightful dimples, was very expressive with his hands – which were usually laden with rings and he had a biting wit. When he delivered a line, he’d lean in and arch a shoulder. He wore snake-skin boots and TANG-orange trousers with T’s trimmed in the same hue. I overhead a conversation where one woman said to the other, sotto-voice, “He’s one of those.” When I asked what ‘one of those’ was, she said straight out, “A poof.” I was confused. A pouf is what we called the ottoman in our living room.

When I was 16, I was invited to model in Paris and encountered a world full of artistic talent where many of the designers, hairdressers, make-up artists and other creatives were like my father’s brother’s wife’s brother. Everyone in that world in Europe was unique. That was why we got booked for covers, ads and photo spreads. One was encouraged to be your authentic self.

That idea stayed with me. You didn’t need to be like anyone. Your responsibility was to be fully you.

In the 80s when Aids was still a death sentence, I lost so many friends from my youth in Paris and their passing left holes.

The world has changed in the intervening years but the framing of the LGBTQ+ community has altered little. There are worlds that exist where gender is invisible. It’s what you do with your life, how you treat people, what you contribute, that is the currency to cachet.

But there are still places where being a woman makes you less, and being part of the LGBTQ+ community is a death sentence.

Ignorance is dangerous. Projection of falsehoods and framing is what society reverts to in the absence of personal knowledge. Not everyone has a father’s brother’s wife’s brother they fall in love with. Stereotypes fill in gaps and those stereotypes are seldom positive. This is why representation is so important.

Not being allowed to love who you want, be that because of religion, culture, class, gender, age – the pain is the same. Being judged negatively for being your authentic self, hurts. It also hurts when our outsides get in the way of people’s perceptions. Being made to feel less because of…. Fill in the blank.

When we are judged for an aspect of ourselves, wealth, poverty, beauty, scars, colour, gender, sexual preference, or being ‘accessible challenged’ – and that becomes our definition – it limits who we are and who we can become. Especially when we are defined by aspects of self we cannot ameliorate; too thin, too fat, too outspoken, big hips, small breasts, meat eater, vegetarian, mother, childless, same sex, trans. If you look hard enough there are so many divisions to make us ‘other’. I’d rather look for overlaps.

When we see the ‘unknown’ as ourselves, understanding spreads and we have compassion and union.

A few decades ago the ‘gay friend’ appeared in film in a profuse way. As Good As It Gets dealt with the bias of a stereotype and the crumbling of that bias through interaction. More recently, Call Me By Your Name, Moonlight and Luca Guadagnino’s Queer, portray love stories between two people who happen to be the same sex. However, those with bias will simply avoid those films, as excellent as they are.

That they are Award contenders may open doors, but I’d like to see another approach included in casting.

It’s great that LGBTQ+ stories have gone from sidekick to centre stage, but there’s a need for a new shift in entertainment and books. The character whose sexuality is irrelevant. Many Black actors have spoken of starring in films where colour was a character – usually through overcoming discrimination. There was a shared irritation that while their colleagues got to talk about their craft, Black actors had to talk about race.

At the Venice Film Festival this year, Daniel Craig insisted that Queer, the film of William S. Burrough’s book of the same name, be told as a love story. The sexual orientation of the character was irrelevant, it was the character itself that appealed. He explained, “The story is about loss, about loneliness, about yearning; it’s about all of these things. If I was writing myself a part and had to tick off all of the things I wanted to do, this (role) would fulfil all of them.” He never mentioned the sexuality of the character.

Similarly, in my storytelling, I wanted to create characters that allow recognition of someone different than your preferences, not as ‘other’, merely as a variable on the human spectrum.

When books, films and theatre showcase LGBTQ+ characters merely as ‘characters’ without making their sexuality an itemised plot point, merely an irrelevant incidental, we will start to see LGBTQ+ representation as it truly is, immaterial to a job, a friendship, a political view. When we stop making LGBTQ+ the only talking point about anyone, then representation spills into the unconscious framing that people fill all variations and you connect with them or you don’t, regardless of belonging to any particular subgroup.

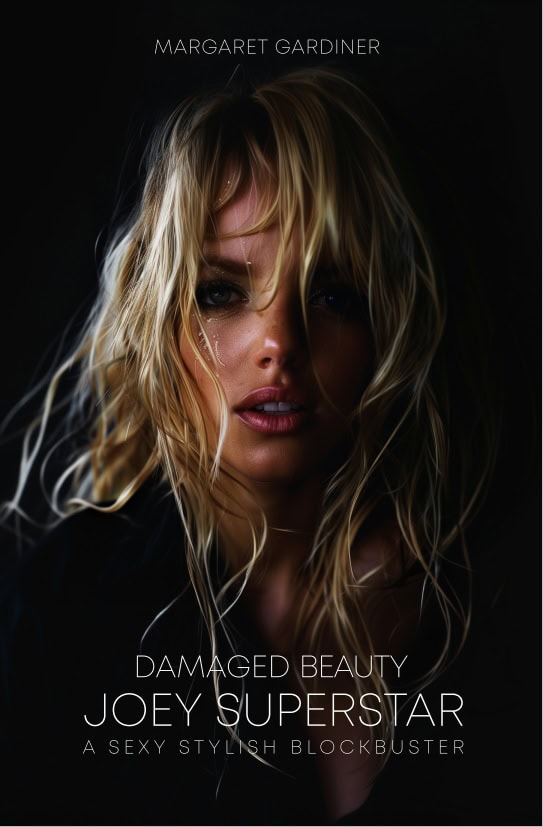

Margaret Gardiner’s debut novel, Damaged Beauty: Joey Superstar (£13.99) is available from all good bookstores. Available at Waterstones.

Instagram: @margaret_gardiner