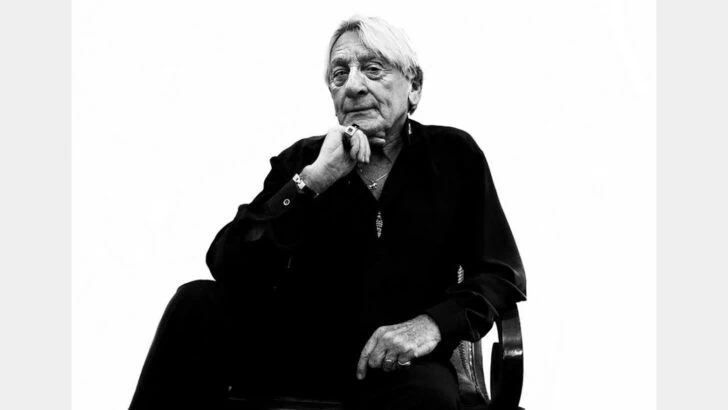

Dr Jonathan Kemp is an author, an academic and a DJ. Ahead of his set at the huge Glamour Factory party this weekend Patrick Cash spoke to him about how all these facets slot together, and his work The Penetrated Male.

By Patrick Cash (Twitter.com/@paddycash)

Tell us a bit about yourself – who is Dr Jonathan Kemp?

Who am I? Good question. It depends on which day of the week, or which head I’m wearing at that time. I’m from Manchester originally, born in Manchester, raised in Cheshire, moved to London in 1989. I am currently working as a teacher of creative writing and I write books and I DJ.

How did you become a doctor?

I did my first degree in the late 80s and by the end of it I was completely turned onto sexual politics and the emerging lesbian/gay politics which predated queer theory, and so when I moved to London I discovered there was an MA in gender studies at Birkbeck part-time which meant I could continue to work, so I did that for two years, and when that finished I inherited some money and I decided to something with it that I wouldn’t have been able to do without the money. And that was a Master of Philosophy in Sussex down in Brighton and when I was finishing that my money was running out and I started working for an academic who lived in Soho and she taught at the Greenwich University and she was very interested in the work that I was doing, and wanted me to do a pHD with her. I said ‘I’d love to, but I don’t have any money left’, and she said there’s a bursary going, why don’t you apply for this bursary? This was the late 90s – ’98 I started my pHD. So I applied for the bursary thinking I was never going to get it, and I got it. It took my five years to do my pHD and I completed my doctorate in 2003.

Who was the academic in Soho?

Her name’s Johnny Golding, she now teaches at Birmingham. She’s an amazing, amazing woman.

Fantastic. And, where did the inspiration for your pHD thesis come from?

Well as I was saying the other night [at a reading of The Penetrated Male], I didn’t set out to write a book on the penetrated male, it was just a couple of years into the research I realised that what all these books I was looking at had in common was that at their very heart was this male body being penetrated in some way, whether it was by the eye, through the ear, or in some cases the anus, but it was more a sense in which the male body was being constructed within discourse as an impenetrable entity and once it was penetrated in some manner it became a psychological and existential assault but it also became the source of a strange, fearful pleasure for the subjects that I was looking at in this literature. So I became interested in that ambiguity around the male body, that ambiguity between being necessarily impenetrable by the way in which he gets constructed into discourse that makes it originate from a penetration, a penetration that has to be subsequently disavowed and vigilantly maintained. So it came by accident, I think like most breakthroughs in research they are happy accidents – you set off in one direction thinking you are going to find a particular thing, then you completely stumble upon something else.

What did you think you were going to find initially?

I was looking to map a kind of genealogy of sexual identity, I was very interested in – I’m a kind of dyed-in-the-wool Foucauldian in many ways and I was looking for the literary equivalent to the genealogy of sexual identity he starts to identify in the late nineteenth century so I was seeing if I could map that through particular literary texts to see how those literary texts interfaced with the more medical, scientific development of sexual identity that was being mapped by other scholars like Foucault and post-Foucauldian scholars like Jeffrey Weeks etc. I really thought – because my bedrock in terms of myself as scholar is very much literature, but also that whole emergence of lesbian and gay, and queer studies is very multi-disciplinary, it covers all sorts of things so even analysis of literary texts became embedded with philosophical and more sociological and more scientific approaches to being human, I guess. So in a way it became multi-disciplinary in a study of literature that allowed to take on a greater breadth and a greater depth. And it wasn’t just looking at a text in isolation, it was looking at the ways in which these texts fit into a whole network of other ways of constructing knowledge.

What would you say is the main angle – I know this is asking you to condense this work of intricacy which you’ve laboured over creating – but the main angle of The Penetrated Male?

I think the main angle really is trying to destabilise monolithic masculinity as a penetrating force that should never be penetrated and can never be penetrated. The angle is to dismantle that, and to identify a moment at which the construction of the modern masculine subject necessitates a penetrability that it has to subsequently disavow. There’s a kind of paradox there that can be used to destabilise what is often seen as natural or self-evident about gender so it’s very much tied in with a lot of feminist and post-structuralist discourses about dismantling binary thinking.

So it’s a subversive work against patriarchal society?

In its own little way.

And what is your opinion on patriarchal society?

I think it’s toxic. Particularly when you harness it to capitalism which is very much a patriarchal economic mindset you get what we’re seeing now happening in the world. What’s interesting for me about the book is reapproaching it for publication last year, thinking ‘oh my god it’s going to be so dated’ and because it’s tied to a very specific time period too, the latest text I actually analyse is 1947, Genet’s ‘Querelle de Brest’, and thinking does it have any relevance now, I’ve got a publisher interested but do I still believe in it as a text? And I actually think it’s more relevant now, now that we see the full impact of a testosterone-driven economy of rampant, unbridled capitalism which dominates nature, dominates other men, dominates women in this absolutely impenetrable way. And so I think that’s the patriarchy that is problematic and I don’t think we can have any other patriarchy, I don’t think we can have a benign, fluffy, cuddly patriarchy – patriarchy by its very nature is about domination. Whether patriarchy is going to be simply flipping the terms of that binary structure whereby women become the dominant force, whether that’s the solution I don’t know. The solution possibly lies in thinking differently than these binaries in the first place. Thinking in a much more intersectional and networked way, connected way, that recognises that if you approach the economy in this particular way then something will suffer, the planet will suffer and human rights will suffer.

Do you think your understanding of this originates from your sexuality? If you were a heterosexual male you might not perceive these problems as explicitly?

Possibly, yeah. Thank god, I’m not but yeah, possibly. I do think that being queer gives you a kind of outsider status, or at least it used to, and I mean now with rampant assimilation and gay people buying into the whole capitalist machinery maybe that outsider status that being gay inevitably brought before kind of no longer brings it. But I think assimilators are deluding themselves. They’re frogs sitting in water as it gets hotter and hotter and cooks them.

How do you see gay culture in 2014, are you optimistic for where it’s going or is it fragmented? How is it different from when you came to London originally?

London itself has changed in the last odd twenty-five years. I’m actually more politically active now than I was then. Then I would go to the odd political rally against Clause 28 and things like that, because that’s what students did in the 80s – I’m not optimistic about many things at the moment. I think the problem with the gay scene in general is that it’s been assimilated into capitalism. The notion that being gay can give you particular insights into how oppression works, I think has been massively diluted – the idea that we’re given rights, the permission to be a solider, the permission to marry, the permission to adopt children, somehow makes us grateful and that gratitude blinds us somehow to the oppressions that are going on elsewhere. But I do think that if I’m optimistic about anything, I’m optimistic about the way that social networking and the internet have enabled information to disseminate outside of mainstream media so I think that is a good way of getting awareness raised, because I think the main problem, as always, is to raise awareness. People being conscious of what’s going on, not just in terms of sexuality, but in general in terms of interconnectedness, that you can buy cheap clothes in the West, means that somebody else somewhere else is suffering massively. I think that kind of awareness is important as well, as thinking ‘we’ve got it all now, but we’re tolerated or accepted or whatever’. I think there is a minority of non-mainstream queers that are active still. The trans movement is very powerful in terms of raising awareness of the multiplicity of genders and the multiplicity of oppressions that go with that, I’m very happy to see that happening, but I think there is a tendency within a particular class perhaps, specifically white gay men, that is a little bit ‘I’m alright, Jack’ and that’s upsetting.

Coming back to The Penetrated Male, do you think we as gay men have a lesser status in society because when we admit ourselves to being gay we admit ourselves to having potentially penetrable bodies? Despite whatever preference you actually have sexuality, but it goes with the idea of being gay.

Possibly. But I think we have a lesser status anyway, and that is tied in with the stereotyping of gay men as effeminate, the stereotyping of gay men as insatiably passive, and I think this in turn is tied in with misogyny. Gay men have a lower status in a patriarchy because women have a lower status in a patriarchy and gay men are kind of affiliated within the patriarchal mindset as somehow being closer to women than they are to men, so I think misogyny plays a massive role in the way that gay men are perceived in our culture.

Do you think effeminacy can be used by gay men as a powerful symbol?

Absolutely, yes. It’s absolutely terrifying to the mainstream, and it’s terrifying to mainstream gay men as well. This is why when you have conservative queer Tory boys, not even queer, gay Tory boys wanting to sideline, marginalise, erase any kind of alternative ways of being, it’s because they are desperate for acceptance and they know acceptance will only come from being as mainstream as possible. And flaming queens with their nail polish and mascara are not mainstream, thank god. If that were the mainstream it’d be a wonderful world to live in.

And with The Penetrated Male you said you published it last year, was it hard to publish before? Was it because of its content do you think?

If it was because of its content, it would be hard for me to say. I don’t know if you’re aware but the process of getting academic books published is they’re sent out to two readers and both reader reports have to be positive. If you get one positive and one negative then the publisher won’t go ahead with it. The mainstream academic presses that I approached, I invariably – and I didn’t approach that many because I was working on London Triptych at the time, when I finished my pHD I had London Triptych kind of half-finished so I was putting a lot of my energies into that, I had an academic job. So I sent it to about three or four publishers over that period of about eight years and it’s very disheartening to get your work rejected anyway, and I would pick myself up, dust myself down and send it to another publisher. I wasn’t perhaps as pro-active as I might have been and the publishers that I sent it to, I would get one absolutely glowing report and then one report that was less than positive, so I was getting a bit disillusioned with it. Then when London Triptych did so well and I started to have a bit more of a public profile I thought well I’ll try this book again, I would like it to be published, it’s kind of sitting on the shelf gathering dust and I still think it’s an important issue even in the ten years since I’d got my pHD nothing else had been published that came close to it. And I was approached by various scholars who’d found it in the library at Greenwich and I’d had extracts from it published in anthologies etc and essays so I was encouraged to think it still had some value and then I found this publisher Punctum in New York and their website said they are specifically looking for manuscripts that mainstream academic presses are not publishing, and I thought ‘well, that sounds perfect’, so I sent them the proposal and went through the usual process of two readers writing reports on it and luckily both reader reports were positive so they said ‘yes, we’re going to go ahead with it’, so I was very happy.

Excellent. And how in general have readers reacted?

Very positively, yeah. The other night when you were there, there was a man in the audience there saying ‘this is long overdue’ and this is a subject that needs to be addressed the more macho the world becomes, and I think that destruction of the planet is kind of tied in to this concept of the impenetrable male. That machismo that is rampant within Wall Street and the financial districts of the world, whether the people populating it are male or female, there are women in there too, it’s not necessarily a biological thing, I think it’s more a constructed notion of what a man is. I think that kind of rampant, domineering notion towards everything and that sense of privilege is very much tied in with a kind of top of the pyramid type of alpha male mentality. People I think are picking up on that as well, people are using it in various ways to think about bodies, to think about how bodies are made intelligible in the world and to think about how bodies are ignored, erased and violently oppressed sometimes. I think if I was going to expand upon the work I’d done in that book I would probably address more trans issues, I think that’s where a lot of interesting intersectional views are going on right now.

Would you expand upon it?

No, I’d probably just do something new that was kind of using some of the insights that was in that book as a kind of platform to start a new kind of study.

I wanted to talk a bit about your fiction writing as well. How does your academic research inform your fiction writing, or does it at all?

I think with the first two books it very much has. With the novel London Triptych and the short-story collection Twenty-Six those three texts almost formed some kind of trilogy for me that represented a period of my life when I was immersed in thinking about bodies and sex and language and philosophy and discovering whole new arenas of ideas, and discovering new writers and new texts through the pHD that were informing what I thought about fiction. I’d always written fiction, ever since I was a kid and I’d been trying to get my fiction published for quite a while, I had a detour into writing for the stage in the mid-90s, I ran a theatre company. But I was always interested in the issues surrounding queer politics, body politics, particularly interested in histories of London and histories of queer subcultures, so those three books definitely form a kind of trilogy of thinking for me, so in that respect those three books represent much more a kind of cross-fertilisation between my academic work and my philosophical work. And the cross-fertilisation isn’t just in terms of ideas and subject matter and content but also in terms of ideas of approaches to language and to how I’m going to write. I’ve tried to make my pHD as non-academic as possible and there are moments in my creative work when it does aspire to some kind of philosophical register so I was interested in that cross-fertilisation, I was reading a lot of books that were neither one thing or another in terms of being a scholarly book or a fictional work, so those three books definitely, I think I’m definitely done with that or doing things a different way, so those three books represent a period of my life when I was immersed in scholarship and also writing creatively as a result of the scholarship that I was immersed in. But how my creative work and any future scholarship will cross-fertilise… I don’t know at the moment, I’m not immersed in any future scholarship towards the book that I’m currently working on.

Can you speak about your new novel at all?

Yeah, it’s a real departure because it’s not got any explicit gay sex in it at all! [Laughs] The central character is a sixty-five-year-old woman and it kind of touches on issues around women in our culture within the last forty years, touching on issues of grief and madness. There is a gay character within the novel, a queer performance artist, but it very much focuses upon this woman’s experiences in her life and what women of her generation were expected to be and do with their lives, and perhaps the psychological price that they pay for that.

And for readers who don’t know, what is London Triptych about?

It’s about the way things change and the way things stay the same for gay men in the city across a hundred years. It traces a kind of genealogy across Oscar Wilde to the 1990s via the repressive 1950s and touches on issues of marginalisation specifically through narratives of gay male prostitution.

And Twenty-Six is your collection of short stories?

There are twenty-six of them, each one is a letter of the alphabet, and whilst it’s not an A-Z of gay sex, language plays a big part in it. The way in which we construct narratives around desire and sex and bodies was very interesting to me. Twenty-Six came immediately after I finished London Triptych when I was still immersed in post-structuralist philosophies of language, so I wanted to write a book that was both representing gay sexual encounters but also somehow undermining how they were represented so it questions itself constantly, almost chases its own tale, it tries to register what desire is but then tries to erase that register or at least destabilise it – you know, ‘did it happen like this?’ Pleasure is very fleeting and language is permanent, pleasure is often quite non-verbal but obviously writing about pleasures and what we do with our bodies requires words, requires language, so those paradoxes and those destabilisations and what we do with our bodies was something I was interested in. I didn’t want to write about sex, I wanted to write about how we write about sex and why we write about sex and maybe even what happens when we do. So it’s a very probing book.

As it were.

As it were.

And how does your academia and your writing tie in to your DJing?

It doesn’t at all. No, I’ve always been absolutely obsessed with music, I think I’m a bit of a frustrated rockstar – I sang in bands a bit in my teens but I was also so achingly shy that I couldn’t overcome that, but I’ve continued to be obsessed with music and DJing is my opportunity to inflict that upon the world to play the music I love at very loud volumes.

Does it infiltrate your fiction at all?

It has done, yes. I reference music in London Triptych and Twenty-Six quite a lot in a very sly way. I steal phrases or appropriate phrases, I’m very interested in the concept of appropriation, I’m interested in the concept of art being recycled, that nothing is really original, that we are not in a vacuum, that we are the product of our influences and that what we write or produce are the product of our influences. I’m very influenced by an American post-punk writer named Kathy Acker. I worked for her briefly in ’96, I met her, she was amazing and very interested in appropriating other texts. It’s very difficult because you know you immediately think that it’s plagiarism and I don’t think that it is plagiarism – if you look at some of the great writers, they’ve all plagiarised or they argue about where they got ideas. And even sometimes if you look at a text like The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot, or Ulysses by James Joyce, not that I would ever want to assume a position on a par with them as a writer, but I think that excites me, it’s a bit like sampling in music and I think we’re in an age where copyright becomes an issue because money is an issue, and the idea that you can steal from somebody else is perceived as a theft, but it’s only perceived as theft in a capitalist economy so it comes back to economics and it comes back to politics, and if you appropriate texts from somebody else, are you stealing it or you paying homage? Is your book gonna make money because of that phrase you used and therefore you owe the person you took that phrase from? I don’t know. And for those with a very vigilant eye and a very broad knowledge of music, particularly lyrics, there are phrases in all of my work that I have lifted, shoplifted from music and I probably will continue to do so. The current novel that I’m working on, because it’s about madness I’ve lifted phrases from other texts about madness, sometimes specifically female madness, texts by Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Jean Rhys etc. etc. but I reference them in the back of the book because my publisher gets very anxious about things like that.

Okay, and talking about the Glamour Factory, you’re one of the main DJs, what can we expect from your set?

Well the theme is the Warhol Factory, but LGBT History Month this year’s main focus is on music which is great for me to do an LGBT History Month event that is about music and recognises that I am a DJ and an author because, not that I’m complaining about the events that I get invited to do, it’s brilliant and I love doing them, but every year since London Triptych has come out I’ve studied readings from that book specifically because it’s about history. But I was approached along with Sadie Lee who is an incredible artist and friend of mine who I run a club night with for nine years called ‘Lower the Tone’ and Joe Pop, another friend of mine, who runs a music night at Retro Bar on Wednesdays called Wild Thing, playing music from many, many decades across time, some of it with a very specific queer reference, some it with a meaning for us, which we’re all very excited about because we’re big Warhol fans. I think for any kid growing up in the 80s, the whole Andy Warhol scene with its New York in the 60s seemed so achingly glamorous with its rentboys and drag queens and drug addicts and freaks, it seemed like the kind of place we wanted to live. So I was obsessed with Warhol and the Warhol films growing up in Manchester, going to the Cornerhouse in Manchester, I mean I think the moment I realised I was actually gay was watching a very naked Joe D’Alessandro on screen in the film Flesh and thinking ‘that’s it’ for me, that’s what I want from now on. Warhol has always been a rather central figure in my life so we’re just going to have fun, really. We’re going to hopefully play records that people want to dance to, there’s music, there’s performance, there’s the inimitable Bird la Bird compering, so I think between us all we’re going to be offering something pretty unique.

Is the Camden Centre going to be transformed into Warholian aesthetics?

Yes, I think so. That’s the plan. But music meant a lot to Warhol too, he did the artwork for the first Velvet Underground album, he did a Rolling Stones album, music was constantly playing in the Factory. The music of the 60s, the popular tunes of the 60s, you know Motown, and we’ll be drawing off that as well, and fashion art, and in some sense a sort of queer politics with a lower case p. Political I think just by existing, the Warhol crowd, they represented and they inhabited a marginal space that was injected into the mainstream because of Warhol’s staus. But really they were very marginal figures, so there was a politics there. Leading by example, almost.

And your edge on your music at the Glamour Factory is queer punk, or is that just for Fagz?

There’ll be some of that, but Fagz is a bit edgier – Glamour Factory is a more diverse knees-up, so there’ll be things played there that we wouldn’t play at Fagz. Fagz has been set up by myself and the glorious creature Matthew Stradling, a very talented artist, who I met by modelling for him twenty odd years ago and we became great friends. He’s immortalised me on canvas many times – we both love Vogue Fabrics and we both decided that the East End needed a bit of a dirty shot of rougher, edgier kind of music than you sometimes find and often gay venues play a much more homogenised, housy style of music and we wanted to go back to that kind of CBGBs grit and thought we’d try out mixing DJs with live music, and we’re on to our third on March 6th. And hopefully it will continue if people want it! We just thought we’d try and offer something different to what was being offered and the kind of night that we’d want to go to.

Finally, what are going to be your Glamour Factory Top 3 Tracks on the 28th?

1. “Got To Be Real” – Cheryl Lynn

3. “Fried My Little Brains” – The Kills

- The Glamour Factory is on Friday 28th February at the Camden Centre, Judd Street (off Euston Road), WC1H 9JE. 8pm-1am, free entry but booking is advised at: www.camdenlgbtforum.org.uk

- Dr Jonathan Kemp’s ‘The Penetrated Male’ is available from Punctum Books, £10. Find out more information about him and all his books at www.jonathan-kemp.com