We review the arty new piece from Steve McLean

Walking down Old Compton Street for the first time has any young man’s heart racing, with a potent scent of excitement in the air. Or maybe what you’re smelling is urine, but what do expect? It’s Soho! It’s this intoxicating mist of dingy alleyways and latent adventure that Steve McLean strives to represent in his return to film after a twenty-four-year hiatus. The comparatively small grid of bars, restaurants and brothels holds a dear place in the hearts of thousands who have made their way through London over the past few decades. Living up to lore that follows this corner of London is not an easy task, but with the likes of Caravaggio, Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud by his side, McLean appeared poised to do it justice.

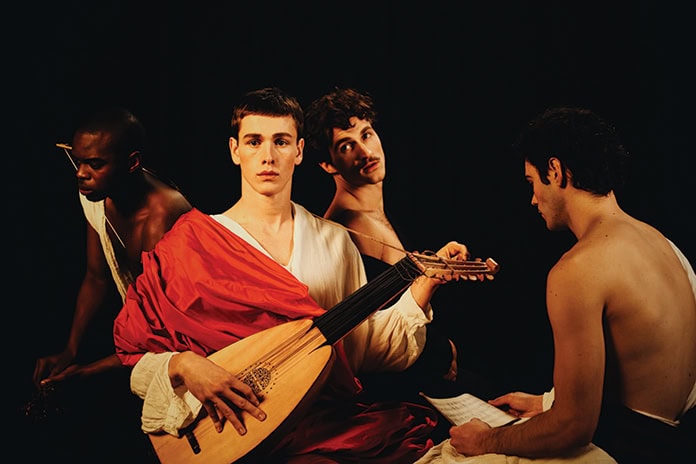

Telling the story of a young Essex boy Jim (Harris Dickenson of Beach Rats fame) travelling to London to make something of himself, who is then rescued after falling on hard times by a group of escort sophisticates, Postcards from London paints a neon-tinted Soho, is rife with possibility. The self-dubbed Raconteurs submerge Jim in a world of baroque art and high culture, which he quickly discovers causes him to faint, catapulting him into the paintings that overwhelm him. Dickenson, though stiff at times, portrays a genuine captivation in the face of these great works of art, yet his yearning to become a muse doesn’t quite translate. His cohort of ignoble intellectuals are powerful presences on screen, and their absence is felt in the more drawn out interactions between Jim and his clients.

These scenes may take place in Soho’s alleyways, bars and hotel rooms, yet McLean takes an ambitious leap to have them unfold in a studio setting, giving just enough to portray the surroundings yet having his characters presented as figures on a dark canvas. His visuals are awe-inspiring, from his re-creation of Caravaggio’s most notable works to create his own works of thought-provoking art of neon signage on dark backgrounds. It is arguably this year’s most visually stimulating film, though scene transitions do the piece a great injustice. One striking image is the neon-garlanded display-windows of the Raconteurs, who sit in an Amsterdam Red Light District set up, each decorated according to their own windows according to their unique styles, like Ken dolls fresh in their boxes. If only we were allowed to see them being played with.

We were left wondering, where is the sex? If these are escorts who specialise in post-coital conversations, why is the audience not privy to the sordid preamble to the talk of fine art? A positive portrayal of sex work is something that is to be applauded, but it’s equally important to delve into the work’s grittier ramifications. There is a complicating of figures that queer high culture hold as numina, notably Saint Sebastian and Caravaggio, who have previously seen queer cinema attention in the works of Derek Jarman, with their truth coming to the forefront to taint their image. Why is our cast of characters not tainted by similar truths?

Postcards from London is an exercise in directorial experimentation that delivers enthralling visuals but lacks progression. The beauty that is achieved is to be admired, though some intrigue in the film’s narrative would make for more engaging viewing. There’s so much potential here, but perhaps it works better as a muse of artistic inspiration rather than being itself a work of art.

Postcards from London is available to order now on Amazon. To find out more about the film head over to PostcardsFromLondon.com or peccapics.com.

by Ifan Llewelyn