The archivist and artist talks being at the forefront of British cultural shift

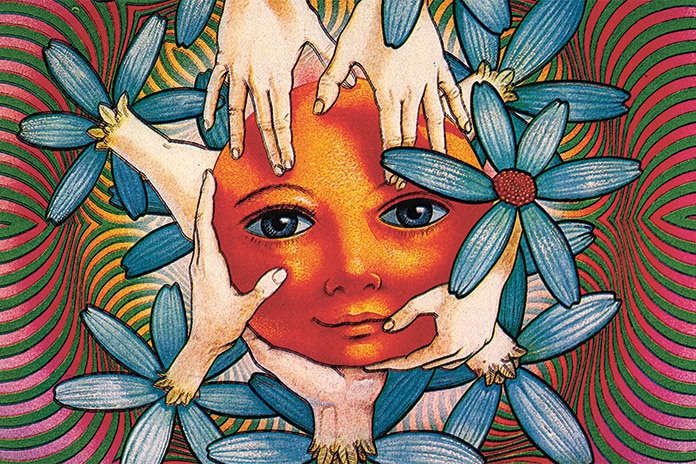

There are very few moments of British nightlife culture that linger in the imagination quite like the rave revolution of the late eighties. They were the years that came to define the following decade and changed the face of partying for an entire generation. Its minimalist production aesthetic thrust the punk DIY mentality into the clubs, forming a movement all its own. After making its way over from Chicago, Acid House set the little known English rave scene alight under the bright glow of the yellow smiley face that became its emblem. Often dubbed the ‘simplest and gentlest of the Eighties youth manifestoes’, its open embrace and egalitarian ethos was a haven for the era’s disenfranchised waifs. One such outcast was Chelsea Louise Berlin who sofa-surfed and squatted her way through one of the most compelling cultural phenomena in recent history.

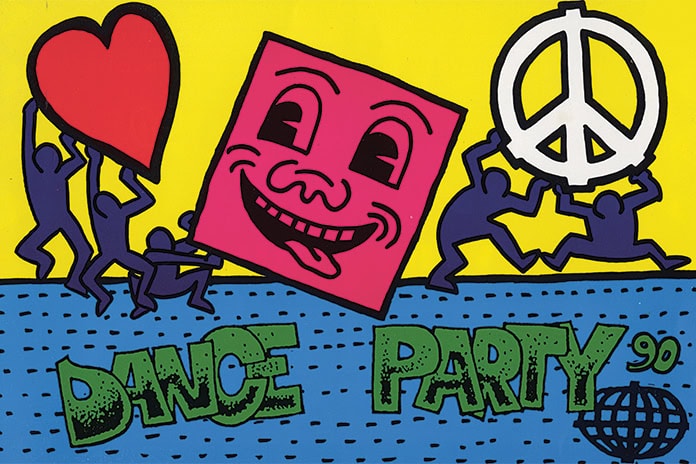

Having witnessed the revolution first hand, Chelsea set about archiving its history through the ephemera she’d collected over the years. With an upcoming exhibition on rave culture, the Saatchi Gallery couldn’t help but get her involved in Sweet Harmony: Rave | Today since her book ‘Rave Art’ served as one of the exhibition’s departure points. We met up with Chelsea to reminisce about her days at the forefront of British nightlife culture.

How did you come to have all these lo-fi visuals in your archive?

One of my passions is collecting. It’s gotten quite out of hand actually because I can’t go anywhere without picking something up and putting it in my handbag. It started when I came out of art school and I was squatting, trying to be a successful artist, living on my wits and I didn’t have much income. The income I did have used to go very fast because I was raving and doing all sorts of weird and wonderful things. I couldn’t afford to have nice art books or things to inspire me, so I kept all the ephemera that came to me from the clubs to postcards, magazines, anything I could lay my hands on that could be useful in the visual library. Because I wasn’t paying for it, I wasn’t concerned if it would suddenly go missing.

How would you describe life pre-rave?

I went to a private school in St Albans, it was horrendous for me. One of the worst experiences of my life. From about the age of fourteen onwards, I hardly turned up there until I had to leave. I’m trans, so growing up in the suburbs in a Jewish middle-class family was quite alienating. There was no one around me I could truly connect with. I knew it was not somewhere I wanted to be forever, knowing who I really was and being unable to be that person was really disconnecting. As I got into my teens it got worse, I’m sure you can imagine being at an all-boys school, what boys talk about at fourteen… I remember telling someone one day at school that I was bisexual, being easier than telling people I was trans, and that was pretty much it. I was bullied remorselessly before I just stopped going to school. After that, I went to the Chelsea School of Art and did a diploma in Art and Design.

Was it then you could explore these underground party scenes?

Yes, I was very rebellious then. I had a lot of issues because I wasn’t allowed to be me around my conservative family and Jewish. For them, it was a Saturday or a Sunday night out, and that just wasn’t me. I had friends from art school that I use to hang out with and I think their influences opened up a different world to me, getting influenced by everyone from goth to heavy metal, to punk, to new wavers, to new age hippies. It was at that time I met Eric Robinson who introduced me to Marilyn and Eddy Armani from Tina Turner’s band, and a bunch of people in the music industry and my life changed completely. I was operating within a completely different echelon. I’d gone from being a wayward person to having an affair with a lot of different people. I was being immersed into gay London life.

It was the lack of convention, the lack of rules. You could be and do whatever you wanted to and nobody would bat an eyelid as long as you weren’t hurting somebody. You could just be yourself. People would be attracted to people for the strangest reasons. Coming from that middle-class suburban background, there was a particular uniform and way of being that was attractive. If you’re from outside that norm you aren’t seen as an attractive character, relationships are hard to formulate and making friends would be more difficult. In the gay scene back in the ‘80s, you could be who you would want to be and there’d always be somebody who’d be interested in you. People would be more open to befriending you, not looking at your differences as something to be maligned.

So you were rubbing shoulders with these influential people, but still, couch surfing? How was trailing that dichotomy?

It was odd. I was lucky, I’m truly blessed to have the friends that I do. Mark Moore from S’Express is still a dear friend, we all still hang out all these years later. Where I was living and what I dressed like wasn’t really important, it was all about the content of your character. Nobody really cared where I lived. Sometimes I’d be staying with friends, sometimes I’d be living in a squat, if I lost the squat then someone would put me up. It was very rare that I actually slept on the street. In four or five years it was probably three nights.

No, I don’t think I can. I’d been spending loads of time at underground clubs that were above a shop on a side street in Notting Hill or in Bow. I ended up coming out a club one night, being given a flyer and decided to go and check it out. The first Acid House club we went to just prior to the raves was on Clink Street, that would be Revolution In Progress, it was all-encompassing, all-inviting. You’d go in there and water condensation would be running down the walls. People would have window panes in their eyes, the gel acid they’d use. Acid House music would be blaring to the Nth degree. It was like being in a movie, it didn’t feel real. The space was derelict, I’m not sure whether they had the right to use it. After the club, we’d be given a flyer to go to a club “somewhere”. Under the West Way, there would be a black cab storage facility under this big dome, and the early parties were there where someone had just set up a system. We’d shoot off to East London, or the Docklands or to Shepherd’s Bush, and you’d turn up at a random location and a rave would be going on. It wouldn’t have been a wear-house in the countryside, that came later. After the venues got too busy, too big and shut down too quickly by the police, they started moving out to bigger venues.

Definitely, I stopped raving when the rest of the country got into it big time. A lot of the other people exhibiting at Sweet Harmony will have been at Spiral Tribe or the others, between ‘92 and ‘98, and I’d long given up raving by then. I’d been doing it pretty much non-stop three or four nights a week non-stop for four or five years and I was exhausted, plus I met someone who wasn’t into dance music at all. It also became very commercial. When Energy became the pioneer rave systems, having fantastic parties in fields and silos and barns, they started advertising for a rave at the Docklands Arena, and when you’re at a venue like that for me it’s like going to see Tina Turner at Wembley Arena. It hasn’t got the buzz, it’s just going to a party to dance. There’s nothing wrong with that, but I wanted to be part of that scene because of its illicit nature. We were being drawn into a lifestyle that few people were living. It wasn’t attractive to me anymore.

Catch Chelsea Louise Berlin’s work at Sweet Harmony: Rave | Today exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery, Chelsea SW3 4RY until the 12th of July.