Why we’re launching Queer Horror Nights!, a new London-based film club dedicated to the darker side of cinema by Token Homo

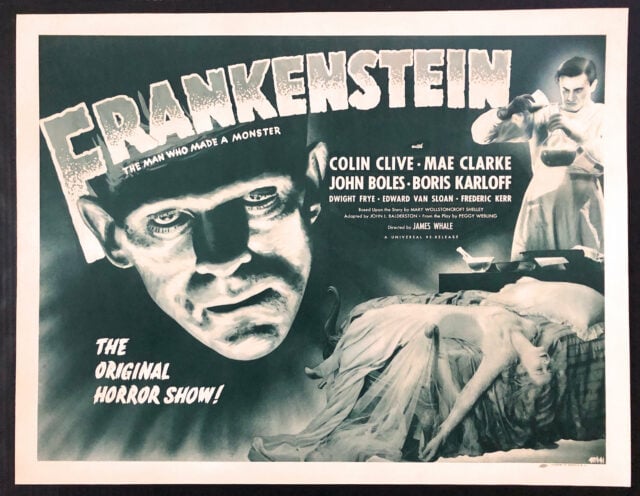

When you tell people that you’re launching a new film club called Queer Horror Nights, you tend to have two reactions. The first is “Oh my god. That sounds awesome. When is it?” The second is, “Oh my god, why are you doing that?!” Now, if you’re in the first camp – and I really hope you are – stop reading this article and book your ticket for our inaugural screening of James Whale’s subversive, queer masterpiece Frankenstein (Sunday 27 February at 17:00 at The Castle Cinema in Hackney). This just leaves me to grapple with the second group…

There are several reasons why horror is our genre of choice, and there are several more reasons for making horror a queer, social event. Put simply, we all need somewhere to go… As lifelong horror fans, my collaborators at Last Frame Club and I staged a trial event last year – a double bill of vampire movies we tenderly titled BITE ME! – to see who was out there. One of the main responses that came back from our sold-out show was that people wanted to see horror films and have a chance to talk about them afterwards. Even amongst our queer extended families it seems, we can’t always come out as horror heads.

There’s a great deal of shared synergy too between the queer and horror communities. One of my favourite quotes about horror comes from the esteemed critic, author and encyclopaedia, Kim Newman, who said in an interview for the Evolution of Horror podcast: “It’s a genre that was named by its enemies… It was called ‘horror’ by people who wanted to suppress it…” This will sound hauntingly familiar to anyone who was reclaimed the Q word, snatching it from the hands of bullies to wear it as a badge of courage.

Historically, queers and horror fans alike have been blamed for many of society’s ills. Indeed, if you impale us both on a spike and play us backwards, you may well hear the decline and fall of Western civilisation. Spinning this back around, watching badly-behaved genre movies becomes a punk rock ritual of rebellion, a canary in the coal mine of societal ‘good taste’. As Blossom Lefcourt puts it when writing about her love of Doris Wishman’s big-busted exploitation films (Double Agent 73 and Deadly Weapons): “I believe the true reason I watch and enjoy Wishman is for the simple fact that I’m not supposed to.” Horror films give us wriggle room when so much of the world is trying to deal in absolutes.

What’s common to every horror screening and to many queer communities is a sense of carnival. The one day, week, night or show where the rules of society are inverted, and we can revel in something that’s a lot less ordinary. And it’s not just us. Drag monstrosity and “wannabe scream queen” Baby Lame is currently rocking the world with Final Baby Girl, a “loud and trashy” fusion of horror, pop culture and satire. This creation of horror show as carnival echoes something the late horror film director Wes Craven said in the documentary The American Nightmare (1999): “What a horror film does is not frighten so much as release fright. It is a vent.”

Carnival enfolds some of the complexities of horror too and finds further parallels in Pride given eternal debates about who gets to be part of that show. The idea of the ‘carnivalesque’ has always had its internal contradictions, a tumultuous celebration of both the dark and the light. You could argue its potency comes from this duality, unruly forces colliding in glorious rainbows of contradictions. I’ve always found the beauty of the LGBTQ+ communities to be our orgiastic sense of difference rather than our uniformity, and yes, this includes an acceptance of the samesex saliva and semen that deliver on our perceived threat to heteronormativity. Californian queercore legends Pansy Division express this succinctly with their activist battlehymn, “Your asshole is political!”.

Whilst horror has its proudly progressive intent, there’s no escaping its deeply regressive side, films where women and queers and people of colour – often in that order – are denigrated, objectified and hacked to pieces before the final reel. Whilst horror exists because of its preparedness to veer to the extremes, it rarely deals in absolutes (and when it does, like the total apocalyptic nihilism of Texas Chain Saw Massacre, it does so for a purpose). Ambivalence, uncertainty and, dare I say it, an old-fashioned usage of the word ‘queer’, abound in horror, giving the genre a constant malleability.

Many will argue that the upturned apple cart gets put right in the final stages of most horror films, when the (queer?) monster gets dispatched and the (often!) heterosexual couple is able to reestablish social norms. Whilst such narratives are common, I never quite understand why they’re seen as a queer betrayal. Every carnival comes to an end. For all we might find solidarity in our queer spaces, many of us still dare not hold hands on the walk home. That constant, bottled-up tension in our lives just makes the need for carnival even more compelling. We will always need to vent.

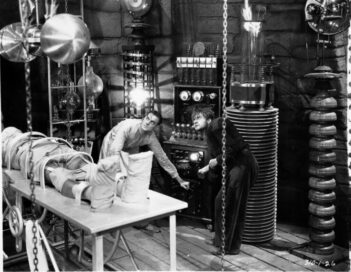

Which brings us to Queer Horror Nights and our opening season of films that have all been directed by out, queer filmmakers. James Whale set the template for this. He was an out gay, British working-class director in 1930s Hollywood, already an establishment success when he made Frankenstein. But he also had to fight studio and state censors on the grounds of his film’s alleged blasphemy and subversive views. By the time of the film’s re-release in 1938, Whale’s career had hit the skids. The film was then butchered by industry censors, brutal cuts made to its original negative that profoundly changed its meaning. And those changes stayed in place until 1985, when surviving film fragments were found during a restoration of the film that would also restore Whale’s vision.

Whale’s Frankenstein sought to contradict the idea of ‘otherness’ being an inherent danger. Instead – channelling Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel and Peggy Webling’s 1927 stage show on which the film was actually based – he tried to show the horror caused by the monster was actually a series of self-inflicted harms triggered by the inhumanity of its creator and the unthinking brutality of society in moral panic. As author Jon Towlson writes in this book Subversive Horror Cinema, Whale’s Frankenstein is truly one of the “great parables of social exclusion”, but only in its original form.

Ostracised from his industry, and following a series of debilitating strokes, Whale wrote a suicide note and was found dead in his own Beverley Hills swimming pool in 1957 (a series of events depicted in the fictional film Gods And Monsters starring Sir Ian McKellen). As a pioneering, visionary, out gay filmmaker who created one of the most queerly subversive and influential films of all time, we think Whale is a horror hero worthy of celebration this LGBT History Month.

We’ve got many more horror films we want to show you. But we’ll start with The Daddy of them all, James Whale’s Frankenstein.

Token Homo x @tokenhomo on IG & TW / tokenhomo.com

Token Homo & Last Frame Club launch their Queer Horror Nights with James Whale’s Frankenstein at The Castle Cinema on Sunday 27 February at 17:00. First floor, 64-66 Brooksby’s Walk, Hackney, London E9 6DA

Booking now: https://thecastlecinema.com/programme/27255/queer-horror-nights-presents-frankenstein/