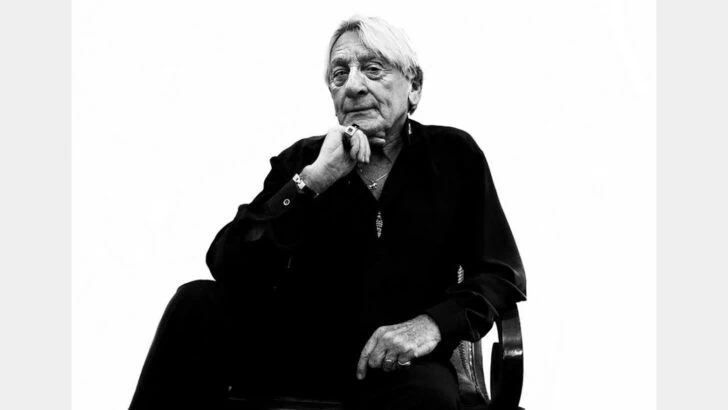

QX Magazine had the great pleasure of talking to Yi Wang, the festival director at Queer East which features in venues across London from 18th April 2023.

Yi tells us about his love of cinema, growing up queer in Taiwan and the influence of queer cinema in the many different countries across East and South East Asia. He also explains why he founded Queer East Festival.

What impact did cinema have on you growing up in Taiwan?

I have always been a keen filmgoer since I was young. Growing up in Taiwan, I was lucky to be able to immerse myself in a vivid and liberal cinema scene, not only international films but also dynamic works made by domestic filmmakers. It might sound quite cliché, but I consider cinema as a window for me, enabling myself to see places that I haven’t been, understand languages that I don’t speak, and most importantly cultures that I might not be familiar with. The films I watched, in a way, they helped shape my identity and played a significant role in my journey of making sense of the world. The idea of being able to experience the power of cinema then became my inspiration to create Queer East here in the UK, and I hope through this that I can share lived experience and cultures that audiences here might not have had a chance to see before.

What impact has queer cinema had across the region?

When we speak about East and Southeast Asia, it is not a singular term with one set meaning, but consists of a wide spectrum of countries that have different languages, cultures, history and perspectives of viewing queerness. Across East and Southeast Asia, the region has a strong and long history of queer filmmaking, and LGBTQ+ representation in the media is strongly linked to reflecting, shaping, and influencing the society and wider public’s views on the LBGTQ+ community.

On one hand, with an increased interest in diversifying queer narratives, we are seeing more and more films go beyond stereotypical portrayals of queer characters and tell stories that cover broader topics addressing societal and political issues, such as the elderly gay community, trans rights, and familial norms. On the other hand, the growing enthusiasm in digging into film archives and restoration has opened up a whole new world of exploring queer cinema history across Asia. Using contemporary queer readings, many early works re-emerge and showcase a surprisingly liberal, fond and diverse queer filmmaking history that has long existed.

Views and opinions judging whether a film is good or bad sometimes might be subjective, but when a diverse queer cinema landscape steps into public view – from independent arthouse films to commercial-oriented BL web series – the invisible becomes visible, providing a chance for audiences to talk about, discuss and debate them. This opening up of conversations is one of the most important roles that queer films play in facilitating a better cultural understanding about queer Asian communities, especially for societies which have a long-standing reticence about homosexuality.

Why does this year’s festival focus on South Korea?

Because everybody’s talking about Korea!?

The global phenomenon of Korean Wave from K-pop to K-drama showcases the country’s hyper energetic and vibrant pop culture and entertainment products. But at the same time, while spotlight is on the mainstream cultural consumption, discussions on issues such as marriage equality and LGBTQ+ rights remain under the radar for a society where public attitudes tend to be conservative.

In light of the country’s recent modest, but significant, advancements in protecting LGBTQ+ rights for same-sex couples, I think it is a great opportunity to shed light on a long history of queer filmmaking which goes way beyond the recent boom of Boy’s Love dramas.

The festival’s 15-film Focus Korea programme offers a glimpse of this lesser-known heritage, spanning work from the 1960s to the present; exploring films that depict the lived experience of Korea’s queer communities through a mixture of genres and art forms. The programme provides audiences a chance to see a snapshot of the country’s diverse queer storytelling and the current queer landscape that is not often represented in mainstream media, providing a more authentic look at the country’s queer heritage.

What are the highlights of the Queer East festival?

I am really tempted to say EVERYTHING!

Besides the Focus Korea, for the very first time, the festival presents two international dance performances: Robin Nimanong’s Cyborg DNA and Choy Ka Fai’s Yishun is Burning. Both pieces draw attention to the intersection of Asianness, queerness and technology, showcasing exciting possibilities of queer storytelling.

Our strong retrospective programme includes the phenomenon musical opera, The Love Eterne made in 1963 in from Hong Kong, marking its 60th anniversary, and a rare screening of the slow-cinema maestro Tsai Ming Liang’s 1992 debut feature, Rebels of the Neon God.

One of my favourites in the festival is the extensive list of short films and moving image work that offers fresh perspectives on artistic queerness from emerging filmmakers, from mind-blowing experimental artist videos, to social-political-focused documentaries. I believe that these programmes provide audiences with a gateway to the modern queer landscape across East Asia, Southeast Asia and beyond.

What do you hope the festival will achieve?

I founded Queer East driven by my personal experience of being Asian, an immigrant, and queer. I often feel that I don’t see my culture and heritage being strongly represented, and sometimes even worse – both are regularly misrepresented in a stereotypical way.

Queer East is a direct response to the systemic lack of Asian representation on the big screen, onstage and behind the scenes. Through our diverse and authentic cultural programme, I hope Queer East can be a platform for under-represented Asian and diaspora communities to share their history, heritage and stories; and for the public to come together and provoke conversations surrounded on what it means to be Asian and queer today.

Advancing LGBTQ+ rights requires a collective approach, and I think it is important for Queer East to join the forces bringing about change in the arts and cultural sector and to enable an open space tackling the inequalities both outside and within the LGBTQ+ communities.

Queer East takes place across London venues from 18-30 April. For tickets and information visit: https://queereast.org.uk/

TICKETS TO QUEER EAST FESTIVAL: https://queereast.org.uk/festival-2023/