In many ways Keith Vaughan (1912-1977) appears to have been a typical, middle-class, British, gay man of his era. Repressed, insecure and tormented, he lived with his mum, loved the ballet and took to the bottle.

Atypically he was a talented and successful artist, not a household name like others of his generation like Sutherland and Bacon, but well-liked and well-paid. He travelled widely, became resident artist at Iowa State University, and ended up with celebrity clients (Dickie Attenborough bought his “Theseus and the Minotaur”) and a couple of homes. Generally speaking Vaughan painted male nudes, landscapes and male nudes in landscapes.

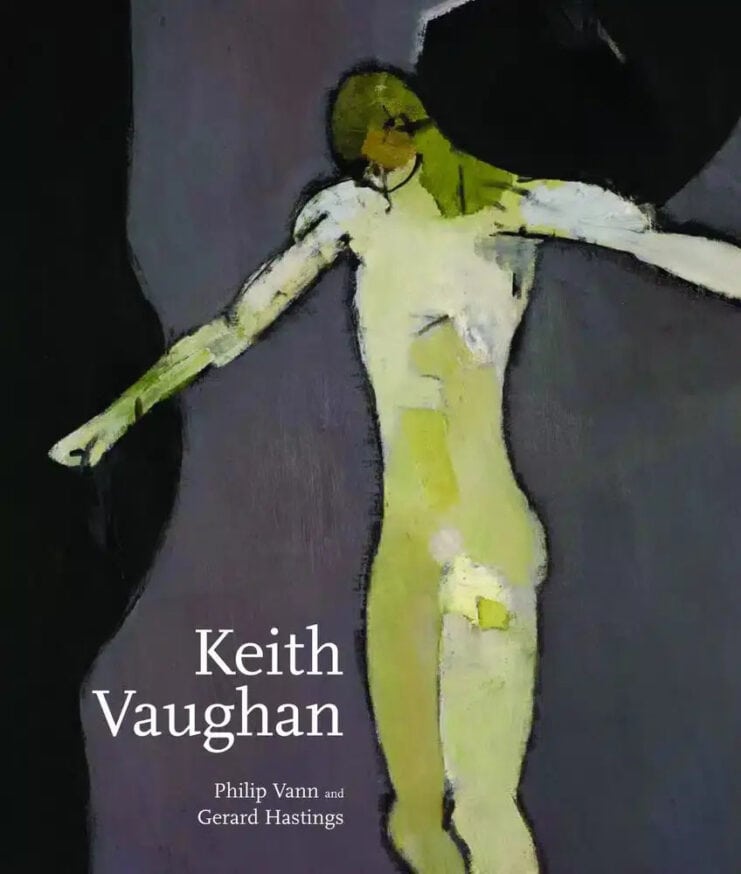

A gorgeous new book, simply titled ‘Keith Vaughan’ (Lund Humphries, £39.99), published to commemorate Vaughan’s centenary, is filled with Vaughan’s oils and gouaches. His work is certainly distinctive.

Almost always the genitals and usually the faces of his masculine but not muscular nudes are blank spaces. Later in his career he broke down his pictures into geometric abstracts.

If Vaughan hadn’t also been a writer, we’d now be guessing what he was trying to communicate. But Vaughan wrote a lot, 61 diaries containing three quarters of a million words, and here he tells us everything society wouldn’t let him express in his art.

“All my miseries and depressions stem from the inability to act out desires when they are felt.”

Keith Vaughan

Vaughan worked in advertising and never trained as an artist. He liked stocky, working-class boys and photographed them naked on the beach. It’s easy to see how these snaps inspired his paintings, one of his few pleasures. “All my miseries and depressions stem from the inability to act out desires when they are felt,” he wrote. “The times I do – such as in painting – I become whole again.” Although he claimed that faces and genitals distracted the viewer, it’s pretty clear that Vaughan’s work represents the isolation he felt as a second-class citizen.

Success brought Vaughan little happiness. “It is difficult to bear in mind,” he wrote, “that with all one’s honours, distinctions, success, etc., one remains a member of the criminal class.” Although he had a long-term partner, he seems never to have been emotionally attached. He died alone, writing in his diary up until the very moment his deliberate drug overdose took effect. Rarely has an artist’s work reflected the cruelty of inhumane law with such poignancy.

‘Keith Vaughan’ by Philip Vann and Gerard Hastings (Lund Humphries, £39.99) is available at www.gaystheword.co.uk