When I was growing up, finding other black gay people felt almost impossible. If you wanted to meet anyone, you had to be brave enough to enter the gay clubs. The so-called “spaces” were never really made for us. I remember the R&B room at Heaven, which felt like the closest thing to a home. Even then, it was a stretch. You could dance to tracks you actually knew, but looking around the room, black faces were few and far between. Half the time, I felt more like an exhibit than part of the crowd.

Dating apps weren’t an escape either. They were another slap in the face. You’d open up a profile and read “no blacks, no fems, no this, no that.” Imagine being young and closeted, looking for connection, and your first introduction to gay dating is rejection printed like it’s policy. Those apps didn’t just fail to bring us together—they reminded us daily that some people didn’t even see us as an option.

So I looked for connection offline, even if it meant wandering into places that didn’t always welcome me. Angel in Stratford was one of my first stops. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was something. I’ll be honest: I ended up giving head in the toilets. As wild as that sounds, he became my boyfriend. Back then, that counted as romance. That was how you had to piece together intimacy: in corners, in shadows, in the spaces where no one thought to look.

Lewisham’s Two8Six, the only gay pub around, was another rite of passage. That’s where I met my first sugar daddy. I didn’t even know what the term meant until he pressed money into my hand after a drink and said, “Get yourself home safe.” That little pub was messy, loud, and often uncomfortable, but for better or worse, it gave me stories I’ll never forget.

Then there was Riverside Tavern in Rochester. That one took everything out of me. I was so far from home, I felt like I had “outsider” stamped on my forehead. I sat outside with a bottle of White Lightning cider and forced it down, just to give myself the courage to walk through the door. Inside, I could feel every eye on me. The room smelled of stale lager and cigarette smoke, and I knew I didn’t belong. The only saving grace was that Samantha Mumba was performing. When she sang, I swear she was singing directly to me and my friend. We were the only black people in the room, and when her eyes scanned the crowd, I felt seen in a way I rarely did back then.

This was the reality of the early 2000s. If you were gay, clubbing was all you had. There was no money for hotels. Most of us were still living at home, hiding from our families. You’d snatch intimacy where you could, whether it was a kiss on the dance floor or a fumbling moment in the toilets. It wasn’t always safe, and it wasn’t always fulfilling, but it was something. You learned to take scraps and call it connection.

Fast forward to now, and things look different, but not completely. We have nights built for us, by us: Jungle Kitty, Connections, Adire Nights, Pussy Palace, Bootylicious. Spaces that put black gay and trans people at the centre. When you walk into these rooms, the energy hits you. The music is ours. The people are ours. The space feels like it’s breathing with you, not against you. Those nights are a lifeline.

But they come with their own challenges. They’re often monthly, so you’re always counting down to the next one. The scene can feel competitive, with everyone trying to look their best, perform their best, and stand out in a room full of people who already shine. Friendships can still be hard to build, especially when the nights are short and the music is loud. And the apps?

They’re still there, still messy, still capable of tearing you down with a single swipe. That’s the thing about connection. It’s not just about sex, or parties, or likes on an app; it’s about belonging. It’s about finding people who get you, who won’t flinch when you tell them your story, who won’t make you feel like the odd one out in a room full of rainbow flags.

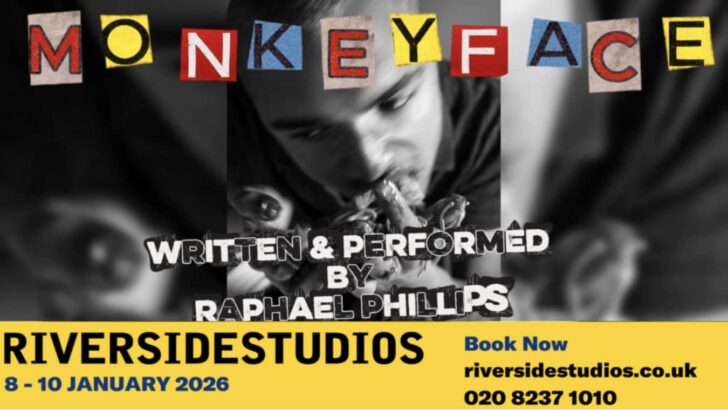

That search for belonging is why I created my show, Limp Wrist and the Iron Fist. It runs at Brixton House from 6 November to 29 November. The show is about joy and struggle, but more than that, it’s about survival. It’s about growing up in a world that didn’t make room for you, and still finding a way to carve out your own space. It’s about those nights in Angel toilets, those bottles of cider in Rochester, those rare moments when a pop star’s gaze feels like a lifeline. And it’s about what comes after, when we finally get to build spaces of our own.

I think back to my younger self, clutching that bottle outside Riverside Tavern, terrified of what I’d find inside. If I could talk to him now, I’d tell him this: the connection you’re searching for is real. It takes time, it takes work, and it’s never simple. But one day, you’ll walk into a room and know that you belong there. And you won’t need White Lightning to convince you.

Limp Wrist & The Iron Fist runs from 6 – 29 November 2025 at Brixton House, 385 Coldharbour Lane, Brixton, London SW9 8GL, United Kingdom.

More about Emmanuel Akwafo

Emmanuel Akwafo is an Olivier-nominated actor, writer and creative. He was awarded a stage debut award in 2023 and was also nominated for outstanding performance at the Black British Theatre Awards. He lives in London.