I’ve always been a sucker for those family-moves-into-spooky-old-house-and-weird-shit-starts-to-happen books and movies that were especially popular in the seventies, shuddering along to The Shining, The Amityville Horror and its umpteen sequels, Poltergeist and its sequels, House (ditto), Burnt Offerings (with Oliver Reed and Bette Davis), The Haunting, The Innocents (screenplay by Truman Capote), The Uninvited and many more; and more recently The Woman in Black, Hereditary, The Conjuring, Insidious and their various and numerous sequels.

Invariably these tales centre on a straight white family, with usually a straight white mum (perceived by others as neurotic; nowadays – a mark of social progress – quite often a single mum) alone at home with the kids, coping increasingly badly with the uncanny goings-on – Mark Danielewski’s meta-novel House of Leaves is a partial exception, but still heterosexual and un-melanated. I thought it would be fun to write a contemporary version of these kinds of stories, utilising all the classic tropes but centring on a multiracial gay family, with the stay-at-home parent (of a young boy) a Black gay man, DuVone, who is recovering from a psychotic break, and whose perceptions are therefore not automatically to be trusted – by others, or by himself (echoing the proto-feminist ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ and The Turn of the Screw).

That simple decision made inevitable a vortex of surrounding non-supernatural conflicts and dissonances, as, post the COVID pandemic, my queer swirl family moves from racially- and sexually-diverse Brooklyn to (fictional) Kwawidokawa County, in all-white, no-gay-pride-parades-here rural Maine. At which point of course all the things one doesn’t need to justify in relation to one’s identity when living in a big city become sudden zones of contestation and anxiety: the responses of in particular their neighbours and the police threaten to corrode and discount my protagonists’ lived experience. The frustrating corollary: the risk of over-interpreting and becoming neurotic in the face incidents of clumsy prejudice voiced by neighbours one has to rub along with, which might, after all, essentially be ‘innocent’; the necessity of, per Du Bois, manifesting double (indeed triple) consciousness as someone gay and as someone Black; and on top of that coping with both the legitimate fears of white (straight) women encountering unfamiliar men and their ‘Karen in the Ramble’-style psychological violence. Well, we’ve all seen the many videos.

My primarily naturalistic approach echoes H P Lovecraft’s definition of a weird tale as one that is very much set in the everyday world, into which (essentially) a single uncanny phenomenon or power or entity intrudes, and must be dealt with – however much a Black gay protagonist would have given Lovecraft heart palpitations.

Vone’s mental health struggles (my writing of which was informed by the psychotic breaks suffered by several dear friends of mine) add a whole other layer of distortion to his perceptions, and his well-meaning white husband Jack has to take a view as to what might be a delusion or (the old accusation laid at any Black person’s door in a predominantly white setting) ‘seeing racism where it isn’t’. This of course requires Jack to get past his own culturally conditioned reflex to see whiteness as the norm, foundational, and all other experiences therefore as no more than distractions from ‘objective reality’ – no easy task. And then there are the strange creatures Vone describes, closing in on the isolated homestead.

I was interested in digging deeper too, into what can be claimed from the polluted well of history – can, for instance, a descendant of slaves ever really feel a nostalgia for, in this case, a Puritan past, in the way his white partner can? What must any Black person, or gay person, set aside to cosplay in history? – that is, if one is taking it more seriously than, say, Bridgerton, or the recent, charming gay episode of Doctor Who, Rogue.

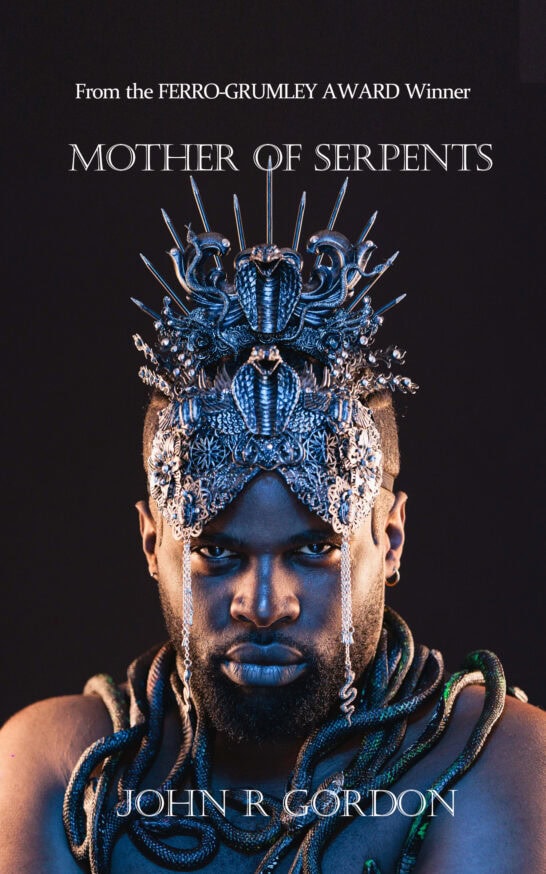

Beneath all that, in writing an America setting, there lies the oftentimes violent displacement of the Native Americans who dwelt there before – the US’s other founding sin (than slavery), and I wanted to connect with that too. Mother of Serpents is about the return of the (literally) buried past, through the awakening, triggered by the arrival of Vone and Jack and in particular their young son Jay-Jay, of two monstrous female entities, the ophidian Skog Madoo and the witch-like Owl Lady; and their alarming and increasingly ferocious battle over the little family in backwoods Maine.

My intention was to in that way write a compelling tale that would feel ‘classic’, with touches of M R James, Henry James, Stephen King, Lovecraft and Algernon Blackwood, but would give in particular Black and gay readers a chance to be the protagonists; ultimately the heroes of the story. That is a simple proposal, but rather pointless unless done well, and so I spent the best part of four years evolving myth and backstory and trying to create something that, while recognisable as genre, would feel original – hopefully sufficiently so that the non-queer and un-melanated would give it a go on its own terms – though Black and/or gay folks remain, as in all my writing, my core intended readership.

There’s been a welcome upsurge recently of Black-centred horror movies – Get Out, quintessetially, but also the satirical The Blackening (which includes a gay character, and has a gay screenwriter) and Lee Daniels’ Exorcist homage The Possession. The HBO series Lovecraft Country (unlike the source book) included an episode featuring Darryl Noah’s Arc Stephens and a queer setting. But I can’t think of a novel that centres a Black gay protagonist (along with his white partner and mixed-race son) as I have done. I hope that Mother of Serpents manages to both feel part of that tradition in a successful way, telling a gripping, glance-over-your-shoulder story, while also presenting a family very different to the usual white and heterosexual one.

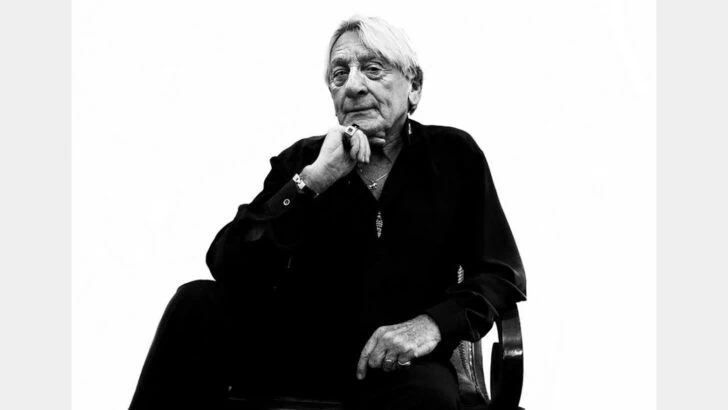

John R. Gordon is a screenwriter, playwright and the author of nine novels, Black Butterflies and Warriors & Outlaws, both of which have been taught in the USA; Faggamuffin, Colour Scheme, Souljah, Drapetomania and the interracial YA romance Hark. He writes for the world’s first Black gay television show, Patrik-Ian Polk’s Noah’s Arc, for which he received an NAACP Image Award nomination. He is the creator of theYemi & Femicomic, for adult readers. His new novel Mother of Serpents (Team Angelica, £13.99) is available from all good book retailers.