If there’s one place in the world where you wouldn’t want to be gay, then it would have to be Uganda. Same-sex activity for females and males is outlawed, with members of the latter gender facing a possible sentence of life imprisonment if they are ‘caught’. Indeed, in 2009, there was an attempt by the country’s MPs to introduce the death penalty for homosexuality.

By Xav Judd

Since 2006, newspapers have routinely published the names, photographs and addresses of LGBTI individuals on their front pages, and called for their execution. Tragically, this fate befell David Kato in 2011. Thus it was at great risk to herself that 28-year-old Cleo Kentaro raised her head above the parapet to detail her experiences of transitioning from a man into a woman.

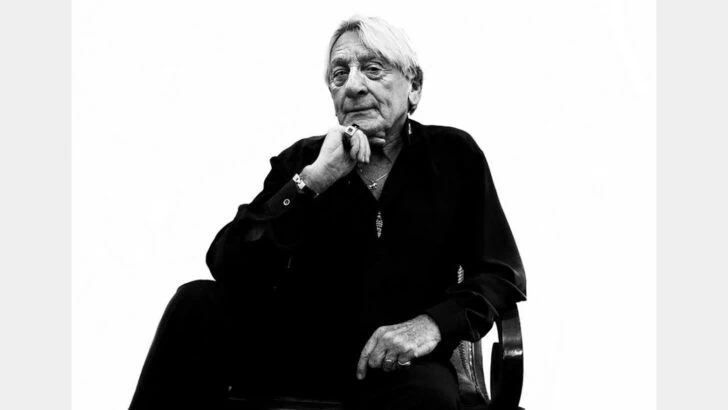

In her nation, there is no clear distinction between sexual orientation and gender identity, so trans people are usually considered to be non-straight. This is a personal journey she has allowed to be captured on celluloid in Jonny von Wallström’s stylish, thought-provoking black and white documentary, The Pearl of Africa. We caught up with the courageous activist to see what growing up in such a bigoted, often dangerous environment was like, and to find out more about the steps involved in her wonderful transformation.

What’s the main reason you wanted your experience to be the subject of a documentary?

In the early 1900s, when Winston Churchill went on an expedition to Uganda, he considered it to be the ‘Pearl of Africa’. And my homeland does have many amazing attributes. However, as a society and a nation we have failed to accept and appreciate our diverse culture, which has meant that those who are thought to be LGBTI are often subjected to extreme abuse. As an activist and out trans person, I believed that it was imperative to change attitudes and perceptions about my part of the community, and debunk the myths that have been perpetuated about us by a biased media, the political elite and religious leaders – often to push their own selfish, pernicious agendas. I hope my particular story can alter the way in which transgender individuals are perceived.

Where in Uganda did you and your relatives live?

I was raised in a polygamous family of fifteen – two mums, a dad and 11 siblings. We resided in a lower middle-class suburb of Kampala called Bakuli.

What age were you when you felt you might be slightly different from everybody else?

In my heart I always sensed that I was a trans person, even though originally I had no idea what that was. Through social interaction at my secondary school, I realised I was not the same as most other people. Later at university, I was introduced to the term transgender, and once I became an activist I started to fully understand my identity.

Were you out at school?

Partly, I guess, yes – because even before I began transitioning, I had an androgynous, slightly effeminate appearance. People behaved in a plethora of ways towards my persona: amusement, annoyance, curiosity. Occasionally there were sexual advances, but a few pupils resorted to verbal abuse.

How did family, friends and the local community react when you came out as a trans person?

I told my family when I was 26. Some of them took it well, but my dad didn’t, so I had to move out. He actually thought I was gay, and to him my orientation was a choice; learned behaviour when I was away doing my undergraduate studies. Nonetheless, the reaction of most of my mates was OK. But the community in Kampala – I was based there when I came out – exhibited a certain amount of hatred: staring, howling, name-calling, et al. It was a difficult time [in my country], because once the new anti-homosexual laws were enacted [2014], it tacitly made it acceptable to be homophobic and transphobic, so several vigilante groups sprung up who wanted to ‘cleanse’ society of the ‘queer filth’.

When did you decide that you actually wanted to transition?

While functioning as an activist during a trip to Nairobi, for the first time I met some African individuals who had gone through this process, which gave me a degree of courage. And they informed me exactly how to go about it – i.e. hormonal therapy and surgery.

“Once the new anti-homosexual laws were enacted, it tacitly made it acceptable to be homophobic and transphobic.“

Who has supported you in your quest to transition?

My mother has been able to empathise with my struggle, so has supported me financially – with my medication expenses – and emotionally by helping me cope with anxiety and depression. In this last regard, some friends have helped, too. The East African LGBTI community has also been quite instrumental in my gender progression, in terms of making me aware of my identity and highlighting the different options that were available to me in respect of my future.

Are there any places for LGBTI people to hang out in Kampala?

There are underground venues, yes. There is one that’s exclusively LGBTI, and then some mixed (bourgeois and expat) places. Nevertheless, in this latter bracket of establishment, discretion is required when showing signs of affection as there are always some homophobes inside.

Are you in a relationship?

Yep, with Nelson Kasaija, my fiancé, a Kenyan who I met over 10 years ago. It has been a testing partnership for both of us: it’s the first one I have had with someone who knows precisely about my gender; and he has had to deal with a cornucopia of difficult emotions to do with his own sexual identity because he is together with a trans person.

Do you know any LGBTI individuals who have been blackmailed?

Yes, more so since the new anti–homosexuality legislation was put into operation. Often, blackmail was used in a political way, to target certain artists, clergymen and MPs in order to stigmatise them by suggesting they associated with so-called ‘sexual deviants’. In general, such a bigoted environment led to a number of LGBTI campaigners being intimidated and outed.

Have you ever been subjected to any abuse?

Several times – verbally, physically and sexually. Depressingly, it came from some of those who were meant to be the closest to me. But I gradually built up an immunity to such prejudice and violence – I had to – and channelled my energy into positive things: study and work, etc. Indeed, rather than dwell on what happened, I have tried to understand how this kind of hatred can develop in others.

Why did you move to Kenya?

I was outed on the front page of some of the tabloids and it went viral, which meant that there was a threat of my partner and me being assaulted, or worse. So we left our jobs and headed to Narobi. Over here, I am a programmes assistant for an NGO that strives for the social equality and equity of the LGBTI community and sex workers.

What would you like to see happen in Uganda in the future, in respect of LGBTI rights?

That everybody in my country can celebrate its rich diversity, rather than persecute anyone who is different. I’d love to witness a time when members of the LGBTI community are not seen as social pariahs; where Ugandans might think about sexuality and gender in a more objective way. Also, I’d like the distinction between trans people and gay individuals to be recognised, hopefully leading to transsexuals being able to get access to hormonal therapy and surgery.

How did you find out that it could be possible to further your transition in Thailand?

Through various forms of social media, and from knowledgeable acquaintances. I have been on feminising hormones for the past three years. I will travel to Bangkok (in 2015) to get gender affirmation surgery.

• Find out more at pearlofafrica.tv