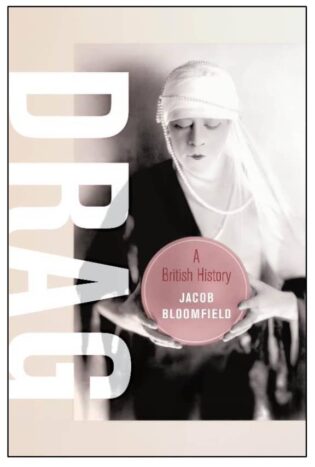

Jacob Bloomfield has just had his book Drag: A British History published. It’s a groundbreaking study that provides fresh perspectives on drag and recovers previously neglected episodes in the art form’s interesting history. It’s also a very compelling read. As QX is very drag-focused and we were keen to learn more, we had a chat with Jacob.

When did you first develop an interest in drag, and have you ever done it?

My academic interest in drag was piqued over ten years ago, during my master’s programme, by an article I read about the 1870/1 Boulton and Park case. Boulton and Park were two London-based drag performers who were arrested while in drag and charged with conspiracy to commit sodomy. They were later acquitted when the prosecution failed to successfully demonstrate that a clear link existed between cross-dressing and homosexuality.

I have done drag before. Scotsgay said of my drag show at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, Songs for Glitter Fetishists, ‘Any show that combines Shirley Bassey, Prince, dildos, Nancy Sinatra, glitter, Kate Bush, hot guitarist, drag, Dolly Parton, kazoos and mildly inappropriate audience participation is on to a winner for me.’ My mother was very proud.

How did you conduct your research for Drag: A British History?

Archives in which I conducted research included the Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection in Bristol, the BFI National Archive, and the V&A Theatre and Performance Archives.

A great resource for theatre historians is the Lord Chamberlain’s Plays at the British Library. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office was responsible for theatre censorship in Britain between 1737 and 1968. During that period, all scripts for new plays, or new additions to old plays, had to be approved by the Office before the plays were staged for the public. As a result, the Lord Chamberlain’s Plays contains original scripts for a great number of shows as well as information about what the censor, and sometimes others, found controversial about a given play. Obviously, I am not in favour of theatre censorship, but a small silver lining to the theatre censorship system is that it left behind a treasure trove of helpful archival material.

What was the most surprising thing you learned in your study of the history of British drag?

When I first embarked on this project, I thought I would mostly be researching niche performances and performers. That was not the case, as it turned out. Many of the drag artists I cover in my book were some of the most popular entertainers of their day.

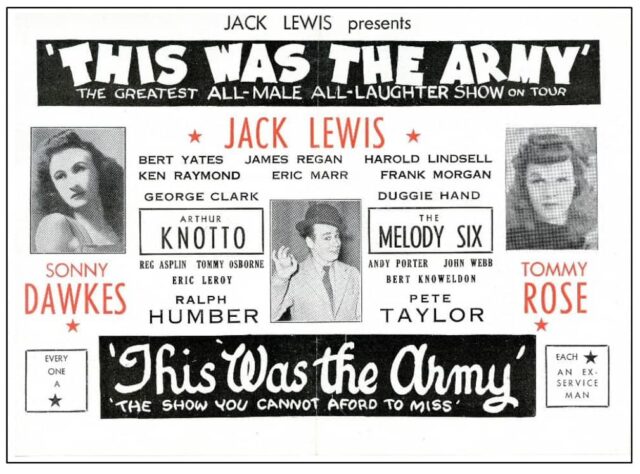

For example, Les Rouges et Noirs, a drag troupe composed of First World War ex-servicemen, starred in one of the very first British-made ‘talkie’ films. They went on to make two more films, and their popular theatre shows toured all over Britain between the wars. Critics and audiences admired the ensemble for their wartime service, but observers also unselfconsciously gushed about how sexy Les Rouges were. One typical review of a Les Rouges show raved that one cast member ‘achieves a wonderful sexual transition, complete in all its details, down to the white-powdered arms and polished manicured finger-nails, the dainty gestures and the positively pretty little affectations of femininity.’

Do you have any favourite drag performers?

There are too many to name here, but some drag performers who knocked my socks off recently (the socks were padding my chest, not on my feet) were the wonderful artists at Diamonds are Forever, a drag night in Kyoto, Japan’s Club Metro.

I also have cherished, if hazy, memories of Cha Cha Boudoir in Manchester. It holds a special place in my heart.

How did drag become associated with queer culture in Britain?

Drag has long held fascination for queer audiences and artists. Furthermore, for some straight audience members, an appeal of drag was that the art form facilitated engagement with the homosexual subculture.

It is difficult to pinpoint a precise moment when drag started to become clearly associated with queer culture. By the early eighteenth century, it was public knowledge that there was a subculture of feminine men – ‘mollies’ – who would cross-dress and have sex with one another.

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there was a sense that drag – on and off stage – was indicative of homosexuality, but that idea was not ubiquitous and drag’s popularity endured despite – and in some cases because of – this. I argue that it was not until the 1970s that drag became definitively, widely, and overtly associated with queer culture and politics.

Do you think drag has contributed to the advancement of LGBT rights?

Yes. Drag has historically played a conspicuous role in LGBT activism. For example, practitioners of ‘radical drag’ disrupted the 1971 inaugural meeting of the Nationwide Festival of Light, an evangelical Christian campaign group, in Westminster Central Hall. At the event, the activists carried out a series of disruptive performances, including dancing the cancan dressed as nuns. Radical drag practitioners also modelled new, queer ways of living. They populated a commune in Notting Hill Gate where they dressed in drag as part of their everyday routine, such as while ‘stagger[ing] down to the newsagents in our high heels and distressed make-up to get the Sunday papers’ after coming down from an LSD trip, according to one participant.

Do you see a significant difference between traditional drag and what is commonly now known as alternative drag?

Traditional ‘female impersonation’ tended to be performed for the purpose of light entertainment. Its intent, usually, was not to challenge the audience intellectually or artistically. The modern alternative and avant-garde forms of drag often aim to challenge or unsettle audiences intellectually and/or artistically.

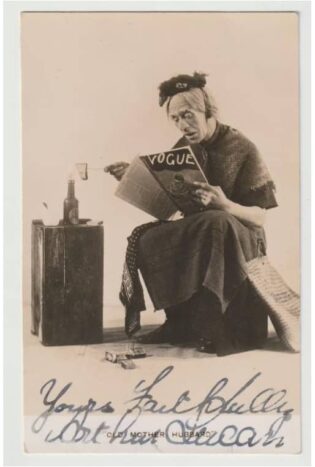

The divide between alternative drag and traditional drag is not always so strict. For example, the films and plays of dame comedian Arthur Lucan, whose heyday was during the interwar and post-Second World War periods, often employed absurdist humour and left-wing political messages that would not be out of place in today’s alternative drag scene.

The early twentieth-century ventriloquist Lydia Dreams was another historical drag artist whose act might gel with the present-day alternative drag scene. Dreams played a nurse tending to a dying patient represented by a dummy. Her act was eerie and goth-like, like something out of a Sisters of Mercy video.

Most art forms have multiple strands, including alternative and mainstream styles. One reason why drag has endured as a popular art form is because it adapts and changes with the times.

What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

Drag is, and has been, a central part of British popular culture.

‘Drag: A British History’ by Jacob Bloomfield is available now and published by https://www.ucpress.edu/

ISBN: 9780520393325

Jacob Bloomfield, Zukunftskolleg Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Konstanz and Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Kent, is the author of Drag: A British History (published by University of California Press). His research is situated primarily in the fields of cultural history, the history of sexuality, and gender history. He is currently working on a book about the historical reception to musician Little Richard in the United States and Europe.