We go behind the scenes at the Tate’s new LGBT exhibition of queer British art

This spring, Tate Britain is holding an exhibition of queer British art; the largest ever collection of its kind. It will incorporate pieces from 1861 (the year in which the death penalty for ‘buggery’ was removed from law) to 1967 (when private homosexual acts were decriminalised). It was a period of time when understandings of sexuality and gender were gradually changing, but were still nowhere near meeting the levels of acceptance we are accustomed to today. The exhibition takes in all kinds of different artistic styles and will include works by artists such as John Singer Sargent, Dora Carrington, Duncan Grant, and David Hockney, who has a separate retrospective exhibition being held concurrently at Tate Britain.

Joe Holyoake spoke to curator Claire Barlow about the upcoming collection and what the pieces tell us about what it was to be queer in this often-fraught time.

There doesn’t seem to be much precedent for this type of exhibition grouped solely around queer art. How long has it been in the works for?

Well, it’s been the last three years of my life! I’m very excited for it. London doesn’t have a permanent space for this sort of queer art and history. Berlin has the Schwules Museum, New York’s got the Leslie Lohman, LA has got things like the Tom of Finland collection. So, it’s a great opportunity to see these pieces all in one place, and hopefully it kick-starts the process for a permanent home.

What sort of works will be on display?

There are all sorts of paintings in different styles, but also photos, personal letters and belongings as well. There are such huge changes in how people perceive themselves, their sexuality, gender, and all of that plays out through the objects of the show. We’re really excited to have a portrait of Oscar Wilde that’s never been seen in Britain before, which is one of only two objects traced from his personal art collection. We’re pairing that with the door of his prison cell, which I found quite heart stopping when they’re put together. He’s just on the cusp of success in the portrait, but then you see how his story ends.

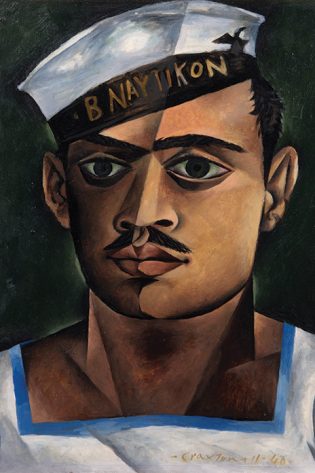

Head of a Greek Sailor

1940

Oil on board

330 x 305 mm

London Borough of Camden

© Estate of John Craxton. All rights reserved, DACS 2016. Photo credit: London Borough of Camden

Is it all defined by tragedy?

Not all of it, but it’s inevitable that there’s going to be quite a bit. One of the first people you meet in the show is Simeon Solomon, who is an established artist, he studied at the Royal Academy, but he’s caught having sex with a man in a public toilet. This destroys his reputation and though some friends and family stick by him, he’s in and out of mental asylums for the rest of his life. Most of the work he does in his later life is quite tortured, but he’s unusual in approaching same-sex desire quite directly in his work. There’s an amazing piece of work called ‘The Bride, The Bridegroom and Sad Love’, where the Bridegroom and Bride are embracing at one side of the image, but the Bridegroom’s hand is holding the hand of Sad Love, looking on eternally, and the positioning of the hands suggest that they were in a relationship together. This was the lot for many queer men in this time, in that you might have same-sex relationships in your teens or early twenties, but the expectation was that you’d have a respectable marriage in later life and leave it all behind. There’s a similar sentiment in this cup we have, which I love. It’s from Charles Ashby, an arts and craft designer, and he’s inscribed it to one of his friends, James Hedlam, on his marriage, and it says ‘on the mournful occasion of his transition into matrimony’. He’s also designed the stem of the cup to have these balls at the bottom and a big, drooping handle, so lots of phallic suggestions there!

Is the exhibition dominated by coded references, or is some of it a bit more open?

It’s difficult to say, as the way we view these items is different to the way people from that time would have looked at them. Some of the stuff looks incredibly explicit to us, but they let it pass without commenting on. There was also stuff that they found really shocking, but it’s difficult to see why now. A lot of queer culture was a bit more open and less guarded though. We’ve dedicated one of the rooms to all the wealth of culture that was bubbling away under the surface. So, there’s theatre, celebrities, music hall, female and male impersonation acts. We have one of Noel Coward’s dressing gowns, and a fantastic pink wig from a 1920’s female impersonation wig worn by Jimmy Slater. It’s from this period that we see some of the more comic female impersonations that would eventually turn into drag.

Wrestlers c.1903,

printed 1911

Photograph, print on salted paper

18.2 x 24 mm

Wilson Centre for Photography, London

Was it difficult to find all the pieces for this show?

There has been a problem of survival with many objects destroyed or lost, often deliberately. There’s a story of the poet John Addington Symonds, who leaves all his papers to his friend Edward Goss, who shares his desires. However, Goss decides to destroy everything apart from the manuscript of his autobiography. Goss then tells Addington Symonds’ granddaughter that he’s done this, expecting her to be delighted he’s protected the family name, and she describes herself being ‘completely nauseated’ by him, as she thought that radical honesty was a major part of his life.

Do you think the idea of the Homintern, where queer people were accepted and even excelled in theatrical and literary circles, also applied to the art world as well?

There’s a stereotype that queer people in the past lived these lonely, isolated lives where they could never express their desires and faded elegantly in the background. But what we’ve found is that there’s a huge range of outcomes. There are undoubtedly some tragic stories, but others found ways of thriving, often in networks of supporters and like-minded people, like the Bloomsbury Set. With other instances, people were often willing to ignore it. Much like Gluck who exhibited at the Fine Art Society for the Royal Family, despite much of her work being very autobiographical and addressing her relationships with various society women. So while we didn’t want to sugar-coat the tragedies, we also wanted to celebrate these successes as well.

Quentin Crisp

1941

Bromide print

National Portrait Gallery (London, UK)

© Estate of Angus McBean /

National Portrait Gallery, London

The last room of the exhibition has got a lot of works by modern queer artists like Francis Bacon and David Hockney. Was it just a pleasant coincidence that the latter’s also got a large show in the same gallery at the same time, or was it planned?

It wasn’t planned as such, as they’re all arranged years in advance, but they’ve just sort of converged on each other. Saying that, I think it works really well together, as you get to see his work in a queer context in our show, but then in a completely different one at his one.

There’s also the Wolfgang Tillmans exhibition on at the Tate Modern as well, which is pretty queer-leaning too. What do you think these shows say about queer art after 1967?

I find it really exciting, because when I was growing up, it would’ve never occurred to me that these august and ‘significant’ museums would be accepting and celebrating my culture. We’ve gone from a period where there were no words, or no positive words at least, for same-sex desire or gender variance, through to a time where it’s being lavishly celebrated. It’s great to see across the whole Tate institution that we’re using the 50-year anniversary to really think the art we have on display and how we can reflect identities, as well as avoiding the old way of looking at queer history, which was just ‘oh here’s a gay man or someone who’s trans or a lesbian’. We’re able to show work which toys with gender fluidity and identities that fall between categories or cut across different ones.

And finally, what’s your personal favourite item from the exhibition?

Oh, that’s such a horrible question, it changes on a daily basis! The piece I have the biggest soft spot for is a group of jewellery that belonged to Michael Field, who was born Katherine Bradley and Edith Cooper. They were these lesbian poets and lovers who develop a joint identity as Michael Field. They still dress in a feminine way, but sometimes they use male pronouns, sometimes female pronouns, and even sometimes a singular male pronoun to refer to the both of them. The jewellery is designed to reflect this joint identity. For me, it’s such a queer story that’s impossible to fit into a box, but is about confidence and celebration, and saying at a time when there weren’t really words for it, this is who we are!

• Queer British Art is at Tate Britain, 5th April-1st October.