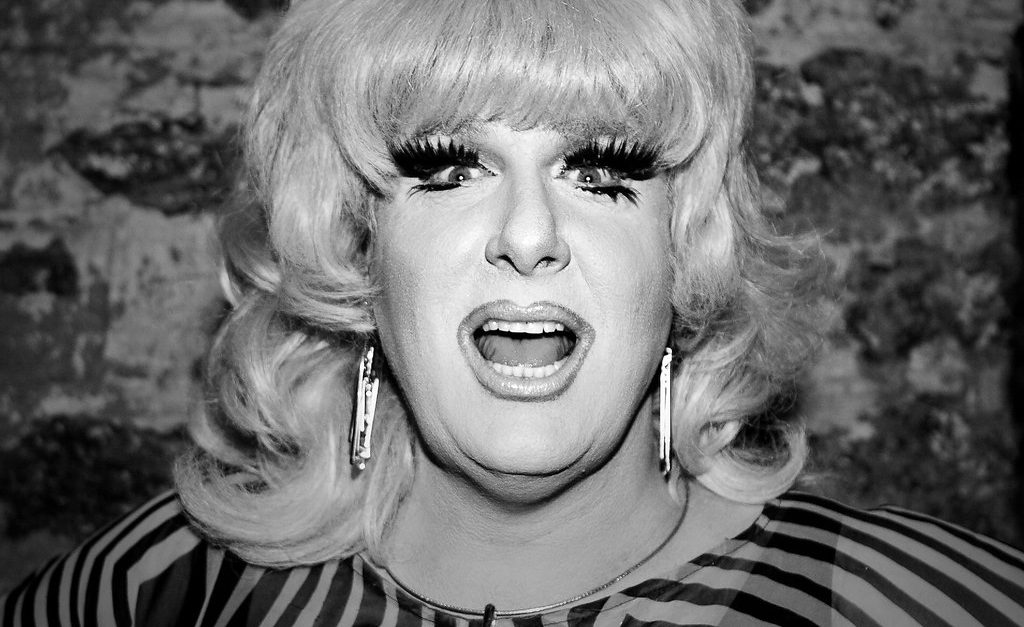

The Eagle catches up with New York City icon Lady Bunny

With those moon-sized blonde wigs, eyelashes that arrive an hour before she does and a sewer mouth to make the late, great Joan Rivers blush in her grave, Lady Bunny is over from New York hawking her latest one-woman show, Pig In A Wig. She’s in Dublin for her gig at Liberty Hall as part of a whistle-stop tour of the UK and Ireland when we speak on the phone, a soft Southern voice more gentle than the visage suggests.

Born Jon Ingle in Tennessee in 1962 to a middle-class academic family, growing up gay in the seventies South wasn’t the torturous ordeal expected. “I struck people as an independent person and they didn’t seem to question me too often,” he says. “I’m not saying I didn’t have a few sticky situations but generally I was pretty much accepted. I went to school with kids I’d grown up with so they all knew me – they knew I was a sissy and they didn’t want me on the sports team but back then people had so little exposure to gay people. Unless you had your tongue hanging out and were being some pervert child molester then you weren’t actually gay.”

His father was posted to Ghana as a professor of History in the early seventies, conversing with his wife to Quakerism and from there sent their son to Bootham, a private English red brick Quaker school in York. The good run of avoiding that decade’s endemic homophobia continued. “You know I got by ok in York,” he says. “They knew I loved to dance so for one of the school dances they cut my head out and put it on John Travolta’s body from Saturday Night Fever with a speech bubble saying, ‘Come on boys!’ It was unbelievably gay.” Well, English private schools. “In my final year we did a school show where it was quite traditional to do drag, so I choreographed a rousing version of Enough Is Enough.” Yep, English private schools.

Moving to Atlanta in the early eighties he met RuPaul, Larry Tee and Lahoma Van Zandt, names that rose together on the city’s club scene before decamping en masse to New York a few years later. The city’s eighties nightlife and music have been mythologised by generations of party people, mined and reworked endlessly by later producers and creatives. Crawling back from near bankruptcy in the seventies, New York was a city of extremes where the “Reagan Rich” rubbed shoulders with pushers and pimps, and the underground spawned fantasy nightlife creatures and musical breakthroughs.

It was at the famous Pyramid club in the mid-eighties that he was given his DJ first break by drag Sister Dimension. “Later I got a job playing at a party called Panty Gurdles and things went from there,” he says. “I’ve never really liked hard music so as the eighties progressed and techno really took over I would be put in the auxiliary room. I always wanted a melody, a vocal and chord changes… there was great R&B at the time and I would play across genres and decades. I’m not the world’s greatest mixer,” he adds laughing, “so I loved to go from a house track to something like Soul II Soul and just make sure every record is good.

“People’s ears were open back then and would have enough respect to give the DJ a chance – crowds now often just walk away if they don’t know it.” He pauses before adding. “I think the success of Horse Meat Disco as a party that now plays around the world indicates that the cooler kids want to open up their ear. I went to their London party one week when I wasn’t DJing and they were playing stuff that I didn’t know which meant the crowd didn’t know it which forces you to listen. To learn.”

As in London with gentrification and development leading to over half the city’s LGBT venues to close, the Giuliani years took their toll in New York. Many of the city’s major venues shut down. The frenetic energy that had pushed through nearly two decades of innovation started to wane which, according to Bunny, made a genuine underground culture difficult to thrive.

“As the clubs have closed it’s been a race to the bottom in many places and that’s why you hear so much top 40 music. They dumb it down, they are not playing the rare cuts,” he says. “Speaking as an elder I remember how rejected we all felt in the eighties and when AIDS was killing us but we had our revenge because we could say our culture was better – and it was.”

Like every queen of a certain age, the virus was an inescapable bleak backdrop to the disco lights and sexual conquests. The creative scenes lost so much and I ask how the crisis personally affected him.

“Oh, I loved it!” He pipes in lightning fast, laughing. “People were dropping like flies and sadly it was the never the ones you wanted to go.” We’re both cackling like two shrews but it’s the style of humour that drew criticism for his acerbic show, TransJester, in 2017. “I mean please, it was terrifying – it was a curse! I don’t know if people realise how profoundly that has influenced the people who survived. I’ll speak to friends of mine from the club world back then and a lot of us will say how we didn’t plan for the future or retirement because we had no idea we’d live through the AIDS crisis. We assumed because all of our friends were dropping that we would die too. I mean I just wanted to lose the weight…” he adds with a wink from across the Irish Sea.

“My shows are always purposefully tasteless,” he continues. “Although Pig In A Wig wasn’t billed as a celebration of politically incorrect humour, it was there and that caused no problem with that in England, Scotland and Ireland. These are just average kids who probably watch Drag Race with some older people thrown. They aren’t people from elite universities who sit and boo hoo over whether someone who has lived their whole life with trans people can say tranny or not.”

It’s a short jump from shimmer tights to Wigstock, the festival he started in 1985 and the wider drag scene. “Instagram drag has shifted the focus on to the appearance rather than the performance,” he says. “I mean honey if you look great and spent hours on your make up with top-of-the-line products then I’ll applaud when you walk out on to the stage – but what are you gonna do to hold my interest?”

There’s a broader swipe at tech culture. “I’ve been walking around London since the weather picked up and I’ve been looking at people who looked so shell shocked, like zombies or something, and then they burst into laughter and I realise they’re connected to some device – or they’re scrolling on Instagram on a beautiful day in the park when people traditionally have got together have fun – do we have a need still to be with each other?

“I DJ’d at Miami Gay Pride: the place was packed, the dance floor was jumping and there’s this guy standing outside the group with his back to the club filming himself singing along to the song with his gay tribe as the backdrop. So even in a big space of people, we find ways to isolate and connect with the friends we aren’t with online often to impress them and make us look like what fun lives we have. So you’ve made yourself a not fun person to be with in real life – when are you ever going to meet these people you are trying to impress? You aren’t but you’re desperate to get more of them.”

We asked if he’s watched Black Mirror.

“No, I avoid mirrors.”

After trialling a few Wigstock parties on cruises around Manhattan the seminal drag festival was revived last year and filmed by HBO for a documentary called Wig out this month. As in the eighties with the shadow of AIDS and his response being to have fun, the put on a show, he feels we are again in a dark period and one reason to it, to bring some fun and celebration to the current climate of anger and fear-based politics. “Everyone thinks Trump is a monster but I don’t see him as that different from any other Republican president, and I’ve lived through several. My issue is how did my side, the Left, lose to Trump? They lost because they are also shit.”

The grievances of people left behind, growing inequality and populist politics bring us to Jenny Livington’s 1989 documentary Paris is Burning. “When you hear Venus Xtravaganza dreaming about a white picket fence we need to realise that while many of us have it to her it was unobtainable, something that she had to dream about or to turn tricks to get. That white picket fence represented safety, prosperity and security and so many now don’t have that,” he says before chipping in with that infectious laugh: “Now I feel guilty about killing her…”

To keep up with Lady Bunny CLICK HERE.